The Firebird with Xian Zhang

Featuring Nimbus Dance and new dance choreography! | New Jersey Symphony Classical

Xian Zhang conductor

Jonathan Spitz cello

Nimbus Dance | Samuel Pott, artistic director & choreographer

New Jersey Symphony

- Johann Sebastian Bach Prelude from Cello Suite No. 2

Behold the majesty and wonder of solo Bach, as Principal Cello Jonathan Spitz spins this mesmerizing theme from thin air.

- Caroline Shaw Valencia

The valencia orange, described as “a thing of nature, yet so complex and extraordinary” inspired this expertly-crafted spring quartet.

- Qasim Naqvi God Docks at Death Harbor (Piano Quintet Version)

Naqvi calls this piece “a vision of our planet years from now … the quiet and peacefulness of a world restoring itself.” Nimbus Dance joins with brand new choreography, titled “Dark Water.”

- Igor Stravinsky Divertimento from The Fairy’s Kiss

Stravinsky loved the Romantics like Tchaikovsky, and created this charming and lilting Divertimento after him.

- Igor Stravinsky Suite from The Firebird

Stravinsky's The Firebird has one of the most exciting finales in all classical music, brought to life here with Nimbus Dance at center stage for the Newark concerts. In a dramatic and inventive departure from traditional renditions, Samuel Pott and Nimbus Dance reimagine The Firebird blending myth and modernity. In this tale, an Icarus-like figure, and a girl from a family in turmoil, seek freedom and liberation through flight.

Performed in Newark and Red Bank

The Firebird with Xian Zhang

Featuring Nimbus Dance and new dance choreography! | New Jersey Symphony Classical

Xian Zhang conductor

Jonathan Spitz cello

Nimbus Dance | Samuel Pott, artistic director & choreographer

New Jersey Symphony

- Johann Sebastian Bach Prelude from Cello Suite No. 2

Behold the majesty and wonder of solo Bach, as Principal Cello Jonathan Spitz spins this mesmerizing theme from thin air.

- Caroline Shaw Valencia

The valencia orange, described as “a thing of nature, yet so complex and extraordinary” inspired this expertly-crafted spring quartet.

- Qasim Naqvi God Docks at Death Harbor (Piano Quintet Version)

Naqvi calls this piece “a vision of our planet years from now … the quiet and peacefulness of a world restoring itself.” Nimbus Dance joins with brand new choreography, titled “Dark Water.”

- Igor Stravinsky Divertimento from The Fairy’s Kiss

Stravinsky loved the Romantics like Tchaikovsky, and created this charming and lilting Divertimento after him.

- Igor Stravinsky Suite from The Firebird

Stravinsky's The Firebird has one of the most exciting finales in all classical music, brought to life here with Nimbus Dance at center stage for the Newark concerts. In a dramatic and inventive departure from traditional renditions, Samuel Pott and Nimbus Dance reimagine The Firebird blending myth and modernity. In this tale, an Icarus-like figure, and a girl from a family in turmoil, seek freedom and liberation through flight.

Performed in Newark and Red Bank

The Firebird with Xian Zhang

Featuring Nimbus Dance and new dance choreography! | New Jersey Symphony Classical

Xian Zhang conductor

Jonathan Spitz cello

Nimbus Dance | Samuel Pott, artistic director & choreographer

New Jersey Symphony

- Johann Sebastian Bach Prelude from Cello Suite No. 2

Behold the majesty and wonder of solo Bach, as Principal Cello Jonathan Spitz spins this mesmerizing theme from thin air.

- Caroline Shaw Valencia

The valencia orange, described as “a thing of nature, yet so complex and extraordinary” inspired this expertly-crafted spring quartet.

- Qasim Naqvi God Docks at Death Harbor (Piano Quintet Version)

Naqvi calls this piece “a vision of our planet years from now … the quiet and peacefulness of a world restoring itself.” Nimbus Dance joins with brand new choreography, titled “Dark Water.”

- Igor Stravinsky Divertimento from The Fairy’s Kiss

Stravinsky loved the Romantics like Tchaikovsky, and created this charming and lilting Divertimento after him.

- Igor Stravinsky Suite from The Firebird

Stravinsky's The Firebird has one of the most exciting finales in all classical music, brought to life here with Nimbus Dance at center stage for the Newark concerts. In a dramatic and inventive departure from traditional renditions, Samuel Pott and Nimbus Dance reimagine The Firebird blending myth and modernity. In this tale, an Icarus-like figure, and a girl from a family in turmoil, seek freedom and liberation through flight.

Performed in Newark and Red Bank

Rachmaninoff Symphony No. 2

New Jersey Symphony Classical

Xian Zhang conductor

Gregory D. McDaniel conductor

Adam Tendler piano

New Jersey Symphony

- Claude Debussy Clair de Lune

Debussy’s original piano solo, Clair de Lune, probably exists in more versions than the Beatles’ “Yesterday” and for good reason, as none before or since have captured in music the true magic of moonlight.

- Nico Muhly Sounding for Piano and Orchestra (New Jersey Symphony Co-Commission)

New York-based pianist Adam Tendler, “currently the hottest pianist on the American contemporary classical scene” (Minneapolis Star Tribune), makes his New Jersey Symphony debut in this hymn tune-filled concerto by broadly popular contemporary composer Nico Muhly.

- Sergei Rachmaninoff Symphony No. 2

Melodies too numerous and beautiful to track—so don’t try. Just let this sweeping Romantic symphony, the inspiration for the song “Never Gonna Fall in Love Again,” work its magic.

Performed in Newark, Princeton and Morristown

Rachmaninoff Symphony No. 2

New Jersey Symphony Classical

Xian Zhang conductor

Gregory D. McDaniel conductor

Adam Tendler piano

New Jersey Symphony

- Claude Debussy Clair de Lune

Debussy’s original piano solo, Clair de Lune, probably exists in more versions than the Beatles’ “Yesterday” and for good reason, as none before or since have captured in music the true magic of moonlight.

- Nico Muhly Sounding for Piano and Orchestra (New Jersey Symphony Co-Commission)

New York-based pianist Adam Tendler, “currently the hottest pianist on the American contemporary classical scene” (Minneapolis Star Tribune), makes his New Jersey Symphony debut in this hymn tune-filled concerto by broadly popular contemporary composer Nico Muhly.

- Sergei Rachmaninoff Symphony No. 2

Melodies too numerous and beautiful to track—so don’t try. Just let this sweeping Romantic symphony, the inspiration for the song “Never Gonna Fall in Love Again,” work its magic.

Performed in Newark, Princeton and Morristown

Rachmaninoff Symphony No. 2

New Jersey Symphony Classical

Xian Zhang conductor

Gregory D. McDaniel conductor

Adam Tendler piano

New Jersey Symphony

- Claude Debussy Clair de Lune

Debussy’s original piano solo, Clair de Lune, probably exists in more versions than the Beatles’ “Yesterday” and for good reason, as none before or since have captured in music the true magic of moonlight.

- Nico Muhly Sounding for Piano and Orchestra (New Jersey Symphony Co-Commission)

New York-based pianist Adam Tendler, “currently the hottest pianist on the American contemporary classical scene” (Minneapolis Star Tribune), makes his New Jersey Symphony debut in this hymn tune-filled concerto by broadly popular contemporary composer Nico Muhly.

- Sergei Rachmaninoff Symphony No. 2

Melodies too numerous and beautiful to track—so don’t try. Just let this sweeping Romantic symphony, the inspiration for the song “Never Gonna Fall in Love Again,” work its magic.

Performed in Newark, Princeton and Morristown

Rachmaninoff Symphony No. 2

New Jersey Symphony Classical

Xian Zhang conductor

Gregory D. McDaniel conductor

Adam Tendler piano

New Jersey Symphony

- Claude Debussy Clair de Lune

Debussy’s original piano solo, Clair de Lune, probably exists in more versions than the Beatles’ “Yesterday” and for good reason, as none before or since have captured in music the true magic of moonlight.

- Nico Muhly Sounding for Piano and Orchestra (New Jersey Symphony Co-Commission)

New York-based pianist Adam Tendler, “currently the hottest pianist on the American contemporary classical scene” (Minneapolis Star Tribune), makes his New Jersey Symphony debut in this hymn tune-filled concerto by broadly popular contemporary composer Nico Muhly.

- Sergei Rachmaninoff Symphony No. 2

Melodies too numerous and beautiful to track—so don’t try. Just let this sweeping Romantic symphony, the inspiration for the song “Never Gonna Fall in Love Again,” work its magic.

Performed in Newark, Princeton and Morristown

Brahms Violin Concerto with Vadim Gluzman

New Jersey Symphony Classical

Lina González-Granados conductor

Vadim Gluzman violin

New Jersey Symphony

- Robert Schumann Overture, Scherzo and Finale

Bursting with a love of life in the months after his marriage to Clara, Robert Schumann created three fantastic movements–one shy of a full symphony but which stand magnificently on their own.

- Gabriela Ortiz Clara

A fascinating depiction of the 19th-century composer-pianist Clara Schumann’s inner life as imagined by one of Mexico's leading contemporary composers.

- Johannes Brahms Violin Concerto

A favorite of New Jersey Symphony audiences, Vadim Gluzman returns with his signature singing tone to play what Brahms began as simply “a few violin passages,” but turned into one of the greatest of all concertos.

Performed in New Brunswick, Red Bank and Newark

Brahms Violin Concerto with Vadim Gluzman

New Jersey Symphony Classical

Lina González-Granados conductor

Vadim Gluzman violin

New Jersey Symphony

- Robert Schumann Overture, Scherzo and Finale

Bursting with a love of life in the months after his marriage to Clara, Robert Schumann created three fantastic movements–one shy of a full symphony but which stand magnificently on their own.

- Gabriela Ortiz Clara

A fascinating depiction of the 19th-century composer-pianist Clara Schumann’s inner life as imagined by one of Mexico's leading contemporary composers.

- Johannes Brahms Violin Concerto

A favorite of New Jersey Symphony audiences, Vadim Gluzman returns with his signature singing tone to play what Brahms began as simply “a few violin passages,” but turned into one of the greatest of all concertos.

Performed in New Brunswick, Red Bank and Newark

Brahms Violin Concerto with Vadim Gluzman

New Jersey Symphony Classical

Lina González-Granados conductor

Vadim Gluzman violin

New Jersey Symphony

- Robert Schumann Overture, Scherzo and Finale

Bursting with a love of life in the months after his marriage to Clara, Robert Schumann created three fantastic movements–one shy of a full symphony but which stand magnificently on their own.

- Gabriela Ortiz Clara

A fascinating depiction of the 19th-century composer-pianist Clara Schumann’s inner life as imagined by one of Mexico's leading contemporary composers.

- Johannes Brahms Violin Concerto

A favorite of New Jersey Symphony audiences, Vadim Gluzman returns with his signature singing tone to play what Brahms began as simply “a few violin passages,” but turned into one of the greatest of all concertos.

Performed in New Brunswick, Red Bank and Newark

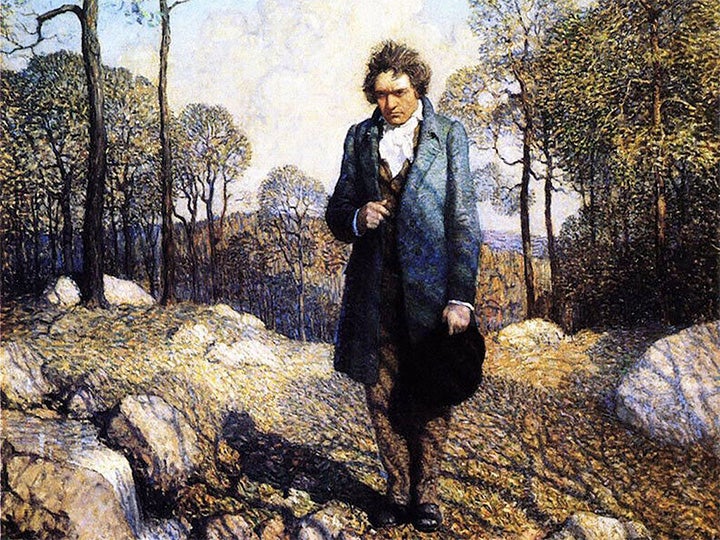

Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony with Xian Zhang

New Jersey Symphony Classical

Xian Zhang conductor

Gregory D. McDaniel conductor

Steven Banks saxophone

Felicia Moore soprano

Kelley O’Connor mezzo-soprano

Issachah Savage tenor

Reginald Smith Jr. baritone

Montclair State University Chorale | Heather J. Buchanan, director

New Jersey Symphony

- Pytor Ilyich Tchaikovsky Polonaise from Eugene Onegin

A lavish ball scene, the dashing hero and heroine twirling in splendor—a fun, festive dance lifted from Tchaikovsky’s opera.

- Billy Childs Diaspora

Inspired by Maya Angelou and other poets, Childs’ new concerto was written for the amazing Steven Banks, who says the music “follows the trajectory of the Black experience from Africa before slave trade to now, going forward in hope.”

- Ludwig van Beethoven Symphony No. 9, “Choral”

The sheer volcanic power of Beethoven’s music makes the Ninth’s message soar. “Brotherhood! Joy!”—our world needs these clarion calls now more than ever.

Performed in Newark and New Brunswick

Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony with Xian Zhang

New Jersey Symphony Classical

Xian Zhang conductor

Gregory D. McDaniel conductor

Steven Banks saxophone

Felicia Moore soprano

Kelley O’Connor mezzo-soprano

Issachah Savage tenor

Reginald Smith Jr. baritone

Montclair State University Chorale | Heather J. Buchanan, director

New Jersey Symphony

- Pytor Ilyich Tchaikovsky Polonaise from Eugene Onegin

A lavish ball scene, the dashing hero and heroine twirling in splendor—a fun, festive dance lifted from Tchaikovsky’s opera.

- Billy Childs Diaspora

Inspired by Maya Angelou and other poets, Childs’ new concerto was written for the amazing Steven Banks, who says the music “follows the trajectory of the Black experience from Africa before slave trade to now, going forward in hope.”

- Ludwig van Beethoven Symphony No. 9, “Choral”

The sheer volcanic power of Beethoven’s music makes the Ninth’s message soar. “Brotherhood! Joy!”—our world needs these clarion calls now more than ever.

Performed in Newark and New Brunswick

Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony with Xian Zhang

New Jersey Symphony Classical

Xian Zhang conductor

Gregory D. McDaniel conductor

Steven Banks saxophone

Felicia Moore soprano

Kelley O’Connor mezzo-soprano

Issachah Savage tenor

Reginald Smith Jr. baritone

Montclair State University Chorale | Heather J. Buchanan, director

New Jersey Symphony

- Pytor Ilyich Tchaikovsky Polonaise from Eugene Onegin

A lavish ball scene, the dashing hero and heroine twirling in splendor—a fun, festive dance lifted from Tchaikovsky’s opera.

- Billy Childs Diaspora

Inspired by Maya Angelou and other poets, Childs’ new concerto was written for the amazing Steven Banks, who says the music “follows the trajectory of the Black experience from Africa before slave trade to now, going forward in hope.”

- Ludwig van Beethoven Symphony No. 9, “Choral”

The sheer volcanic power of Beethoven’s music makes the Ninth’s message soar. “Brotherhood! Joy!”—our world needs these clarion calls now more than ever.

Performed in Newark and New Brunswick

Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony with Xian Zhang

New Jersey Symphony Classical

Xian Zhang conductor

Gregory D. McDaniel conductor

Steven Banks saxophone

Felicia Moore soprano

Kelley O’Connor mezzo-soprano

Issachah Savage tenor

Reginald Smith Jr. baritone

Montclair State University Chorale | Heather J. Buchanan, director

New Jersey Symphony

- Pytor Ilyich Tchaikovsky Polonaise from Eugene Onegin

A lavish ball scene, the dashing hero and heroine twirling in splendor—a fun, festive dance lifted from Tchaikovsky’s opera.

- Billy Childs Diaspora

Inspired by Maya Angelou and other poets, Childs’ new concerto was written for the amazing Steven Banks, who says the music “follows the trajectory of the Black experience from Africa before slave trade to now, going forward in hope.”

- Ludwig van Beethoven Symphony No. 9, “Choral”

The sheer volcanic power of Beethoven’s music makes the Ninth’s message soar. “Brotherhood! Joy!”—our world needs these clarion calls now more than ever.

Performed in Newark and New Brunswick

Star Wars: The Force Awakens in Concert

New Jersey Symphony at the Movies

Constantine Kitsopoulos conductor

New Jersey Symphony

Thirty years after the defeat of the Empire, Luke Skywalker has vanished, and a new threat has risen: The First Order, led by the mysterious Supreme Leader Snoke and his enforcer, Kylo Ren. General Leia Organa’s military force, the Resistance—and unlikely heroes brought together by fate—are the galaxy’s only hope. Experience the complete film with the New Jersey Symphony performing John Williams’ thrilling score live.

Performed in Red Bank, Morristown, Newark and New Brunswick

Star Wars: The Force Awakens in Concert

New Jersey Symphony at the Movies

Constantine Kitsopoulos conductor

New Jersey Symphony

Thirty years after the defeat of the Empire, Luke Skywalker has vanished, and a new threat has risen: The First Order, led by the mysterious Supreme Leader Snoke and his enforcer, Kylo Ren. General Leia Organa’s military force, the Resistance—and unlikely heroes brought together by fate—are the galaxy’s only hope. Experience the complete film with the New Jersey Symphony performing John Williams’ thrilling score live.

Performed in Red Bank, Morristown, Newark and New Brunswick

Star Wars: The Force Awakens in Concert

New Jersey Symphony at the Movies

Constantine Kitsopoulos conductor

New Jersey Symphony

Thirty years after the defeat of the Empire, Luke Skywalker has vanished, and a new threat has risen: The First Order, led by the mysterious Supreme Leader Snoke and his enforcer, Kylo Ren. General Leia Organa’s military force, the Resistance—and unlikely heroes brought together by fate—are the galaxy’s only hope. Experience the complete film with the New Jersey Symphony performing John Williams’ thrilling score live.

Performed in Red Bank, Morristown, Newark and New Brunswick

Star Wars: The Force Awakens in Concert

New Jersey Symphony at the Movies

Constantine Kitsopoulos conductor

New Jersey Symphony

Thirty years after the defeat of the Empire, Luke Skywalker has vanished, and a new threat has risen: The First Order, led by the mysterious Supreme Leader Snoke and his enforcer, Kylo Ren. General Leia Organa’s military force, the Resistance—and unlikely heroes brought together by fate—are the galaxy’s only hope. Experience the complete film with the New Jersey Symphony performing John Williams’ thrilling score live.

Performed in Red Bank, Morristown, Newark and New Brunswick

Youth Orchestra Spring Concert

Two performances in one day! | Youth Orchestra Showcase

Diego García artistic director, The Anna P. Drago Chair

Terrence Thornhill associate conductor & curriculum specialist

New Jersey Symphony Youth Orchestra, The Resident Youth Orchestra of the John J. Cali School of Music at Montclair State University

The New Jersey Symphony Youth Orchestra will showcase 300 talented young musicians across two performances as part of their annual Spring Concert on Sunday, April 27 in Newark. Experience vibrant performances and celebrate the achievements of the 2024–25 season, including a special tribute to the graduating seniors.

Performed in Newark

Youth Orchestra Spring Concert

Two performances in one day! | Youth Orchestra Showcase

Diego García artistic director, The Anna P. Drago Chair

Terrence Thornhill associate conductor & curriculum specialist

New Jersey Symphony Youth Orchestra, The Resident Youth Orchestra of the John J. Cali School of Music at Montclair State University

The New Jersey Symphony Youth Orchestra will showcase 300 talented young musicians across two performances as part of their annual Spring Concert on Sunday, April 27 in Newark. Experience vibrant performances and celebrate the achievements of the 2024–25 season, including a special tribute to the graduating seniors.

Performed in Newark

Haydn’s Creation

New Jersey Symphony at the Cathedral

John J. Miller conductor

Lorraine Ernest soprano

Theodore Chletsos tenor

Jorge Ocasio bass-baritone

The Archdiocesan Festival Choir

The Cathedral Choir

New Jersey Symphony

The Cathedral Basilica of the Sacred Heart in Newark, NJ invites all to experience the music of Franz Joseph Haydn’s The Creation, featuring The Archdiocesan Festival Choir, The Cathedral Choir, vocal soloists and the New Jersey Symphony with John J. Miller conducting.

Performed in Newark

The Music of Led Zeppelin

Featuring hits like “Kashmir,” “Black Dog,” “Stairway to Heaven” and more!

Brent Havens conductor & arranger

Windborne Music Group

Justin Sargent vocalist

New Jersey Symphony

The New Jersey Symphony and Windborne Music Group bridge the gulf between classical music and rock n’ roll to present The Music of Led Zeppelin, celebrating the best of the legendary classic rock group. Amplified with full-on guitars and screaming vocals, sing and dance along as Led Zeppelin’s “sheer blast and power” is put on full display riff for riff with new musical colors. Timeless hits like “Kashmir,” “Black Dog,” “Stairway to Heaven” and more will get you on your feet in this special concert you don’t want to miss!

Performed in Englewood and New Brunswick

The Music of Led Zeppelin

Featuring hits like “Kashmir,” “Black Dog,” “Stairway to Heaven” and more!

Brent Havens conductor & arranger

Windborne Music Group

Justin Sargent vocalist

New Jersey Symphony

The New Jersey Symphony and Windborne Music Group bridge the gulf between classical music and rock n’ roll to present The Music of Led Zeppelin, celebrating the best of the legendary classic rock group. Amplified with full-on guitars and screaming vocals, sing and dance along as Led Zeppelin’s “sheer blast and power” is put on full display riff for riff with new musical colors. Timeless hits like “Kashmir,” “Black Dog,” “Stairway to Heaven” and more will get you on your feet in this special concert you don’t want to miss!

Performed in Englewood and New Brunswick

Xian Conducts Mozart

New Jersey Symphony musicians take the spotlight!

Xian Zhang conductor

Eric Wyrick violin

Francine Storck violin

New Jersey Symphony

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Eine kleine Nachtmusik

Mozart may have tossed this off for a Viennese party one evening, but there is no piece more charming and beguiling than his “a little night music.”

- Johann Sebastian Bach Double Concerto for Two Violins

The spotlight’s on our two superstar principal violins, Eric Wyrick and Francine Storck, in perhaps the most beautiful duet ever created.

- Michael Abels Delights and Dances

Delight in this imaginative, bluesy work for solo string quartet and string orchestra, with New Jersey Symphony’s own musicians taking the spotlight in a series of captivating solos.

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony No. 35, “Haffner”

Mozart had intended to jot down a little occasional piece, but brilliant music kept pouring out of his pen until he’d made a dazzling full-fledged symphony, one of his best.

Performed in Princeton and Newark

Discover Mozart & Bach

New Jersey Symphony Family Concert:

A Music Discovery Zone

Xian Zhang conductor

Gregory D. McDaniel conductor

Eric Wyrick violin

Francine Storck violin

Annamaria Witek cello

New Jersey Symphony

Discover what makes a live orchestra concert so special. We’ll take a deep dive into works by Mozart, as well as J.S. Bach’s incredibly famous Double Concerto for Two Violins. Also featured on the program is 2024 Henry Lewis Concerto Competition winner, cellist Annamaria Witek. Inspired by Leonard Bernstein’s masterful way of putting young audiences at the center of music-making, this interactive concert will feature inside tips, listening cues and fun facts that make for the perfect Saturday afternoon family outing!

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Selection from Eine kleine Nachtmusik

- Camille Saint-Saëns Selection from Cello Concerto No. 1

- Johann Sebastian Bach Double Concerto for Two Violins

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony No. 35, “Haffner”

Performed in Newark

Xian Conducts Mozart

New Jersey Symphony musicians take the spotlight!

Xian Zhang conductor

Eric Wyrick violin

Francine Storck violin

New Jersey Symphony

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Eine kleine Nachtmusik

Mozart may have tossed this off for a Viennese party one evening, but there is no piece more charming and beguiling than his “a little night music.”

- Johann Sebastian Bach Double Concerto for Two Violins

The spotlight’s on our two superstar principal violins, Eric Wyrick and Francine Storck, in perhaps the most beautiful duet ever created.

- Michael Abels Delights and Dances

Delight in this imaginative, bluesy work for solo string quartet and string orchestra, with New Jersey Symphony’s own musicians taking the spotlight in a series of captivating solos.

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony No. 35, “Haffner”

Mozart had intended to jot down a little occasional piece, but brilliant music kept pouring out of his pen until he’d made a dazzling full-fledged symphony, one of his best.

Performed in Princeton and Newark

Xian Conducts Mozart

New Jersey Symphony musicians take the spotlight!

Xian Zhang conductor

Eric Wyrick violin

Francine Storck violin

New Jersey Symphony

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Eine kleine Nachtmusik

Mozart may have tossed this off for a Viennese party one evening, but there is no piece more charming and beguiling than his “a little night music.”

- Johann Sebastian Bach Double Concerto for Two Violins

The spotlight’s on our two superstar principal violins, Eric Wyrick and Francine Storck, in perhaps the most beautiful duet ever created.

- Michael Abels Delights and Dances

Delight in this imaginative, bluesy work for solo string quartet and string orchestra, with New Jersey Symphony’s own musicians taking the spotlight in a series of captivating solos.

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony No. 35, “Haffner”

Mozart had intended to jot down a little occasional piece, but brilliant music kept pouring out of his pen until he’d made a dazzling full-fledged symphony, one of his best.

Performed in Princeton and Newark

2025 Spring into Music Gala & Auction

Gala Reception and Dinner, Concert and Auction

Join the New Jersey Symphony and an array of cultural, social, business and civic leaders for an unforgettable evening of fine dining and entertainment as we honor former Governor Thomas H. Kean and his dedication to the performing arts industry in New Jersey. The event will feature a lavish cocktail reception with a few dazzling surprises, a dinner with a private performance featuring members of the New Jersey Symphony and students of the New Jersey Symphony Youth Orchestra and a silent auction.

Presented in West Orange

Rachmaninoff and Shostakovich

Season Finale | New Jersey Symphony Classical

Xian Zhang conductor

Conrad Tao piano

New Jersey Symphony

- Sergei Rachmaninoff Piano Concerto No. 2

No piece has introduced and won more people to classical music than Rachmaninoff’s magnificent work for piano and orchestra.

- Dmitri Shostakovich Symphony No. 5

When Shostakovich’s Fifth received a half-hour standing ovation at its premiere, the world knew that a classic was born—and it remains a landmark work for the virtuoso orchestra.

Performed in Morristown, Princeton, Red Bank and Newark

Rachmaninoff and Shostakovich

Season Finale | New Jersey Symphony Classical

Xian Zhang conductor

Conrad Tao piano

New Jersey Symphony

- Sergei Rachmaninoff Piano Concerto No. 2

No piece has introduced and won more people to classical music than Rachmaninoff’s magnificent work for piano and orchestra.

- Dmitri Shostakovich Symphony No. 5

When Shostakovich’s Fifth received a half-hour standing ovation at its premiere, the world knew that a classic was born—and it remains a landmark work for the virtuoso orchestra.

Performed in Morristown, Princeton, Red Bank and Newark

Rachmaninoff and Shostakovich

Season Finale | New Jersey Symphony Classical

Xian Zhang conductor

Conrad Tao piano

New Jersey Symphony

- Sergei Rachmaninoff Piano Concerto No. 2

No piece has introduced and won more people to classical music than Rachmaninoff’s magnificent work for piano and orchestra.

- Dmitri Shostakovich Symphony No. 5

When Shostakovich’s Fifth received a half-hour standing ovation at its premiere, the world knew that a classic was born—and it remains a landmark work for the virtuoso orchestra.

Performed in Morristown, Princeton, Red Bank and Newark

Rachmaninoff and Shostakovich

Season Finale | New Jersey Symphony Classical

Xian Zhang conductor

Conrad Tao piano

New Jersey Symphony

- Sergei Rachmaninoff Piano Concerto No. 2

No piece has introduced and won more people to classical music than Rachmaninoff’s magnificent work for piano and orchestra.

- Dmitri Shostakovich Symphony No. 5

When Shostakovich’s Fifth received a half-hour standing ovation at its premiere, the world knew that a classic was born—and it remains a landmark work for the virtuoso orchestra.

Performed in Morristown, Princeton, Red Bank and Newark

How to Train Your Dragon in Concert

New Jersey Symphony at the Movies

Lawrence Loh conductor

New Jersey Symphony

DreamWorks’ How to Train Your Dragon is a captivating and original story about a young Viking named Hiccup, who defies tradition when he befriends one of his deadliest foes—a ferocious dragon he calls Toothless. Together, these unlikely heroes must fight against all odds to save both their worlds. Featuring John Powell’s Oscar-nominated score performed live to picture, How to Train Your Dragon in Concert is a thrilling experience for all ages.

Performed in Morristown, New Brunswick and Newark

How to Train Your Dragon in Concert

New Jersey Symphony at the Movies

Lawrence Loh conductor

New Jersey Symphony

DreamWorks’ How to Train Your Dragon is a captivating and original story about a young Viking named Hiccup, who defies tradition when he befriends one of his deadliest foes—a ferocious dragon he calls Toothless. Together, these unlikely heroes must fight against all odds to save both their worlds. Featuring John Powell’s Oscar-nominated score performed live to picture, How to Train Your Dragon in Concert is a thrilling experience for all ages.

Performed in Morristown, New Brunswick and Newark

How to Train Your Dragon in Concert

New Jersey Symphony at the Movies

Lawrence Loh conductor

New Jersey Symphony

DreamWorks’ How to Train Your Dragon is a captivating and original story about a young Viking named Hiccup, who defies tradition when he befriends one of his deadliest foes—a ferocious dragon he calls Toothless. Together, these unlikely heroes must fight against all odds to save both their worlds. Featuring John Powell’s Oscar-nominated score performed live to picture, How to Train Your Dragon in Concert is a thrilling experience for all ages.

Performed in Morristown, New Brunswick and Newark

TwoSet Violin with the New Jersey Symphony

Part of the TwoSet Violin World Tour

TwoSet Violin

New Jersey Symphony

World-famous YouTube classical music comedy duo TwoSet Violin take the stage with the New Jersey Symphony for a wide-ranging night of musical fun! Violinists Eddy Chen and Brett Yang will take their unique brand of earnest and silly musical comedy to a new level in this performance, with the backing of a full symphony orchestra.

Performed in Newark

Opening Night Celebration

Dinner Prelude, Concert and After-Party

You are invited to the New Jersey Symphony’s 2025 Season Opening Celebration honoring Xian Zhang’s 10th season as Music Director. Guests will enjoy an elegant dinner prelude, the season opening concert featuring Music Director Xian Zhang, guest artist Joyce Yang and the New Jersey Symphony and a dessert after-party.

Presented in Newark

Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No. 1

Opening Weekend | New Jersey Symphony Classical

Xian Zhang conductor

Joyce Yang piano

New Jersey Symphony

- Jessie Montgomery Hymn for Everyone

We launch the season with Montgomery’s open-arms musical welcome. In her Hymn for Everyone you’ll hear an echo of “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” often called the Black National Anthem.

- Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto No. 1

Slammed as a flop at its premiere, Tchaikovsky more than had the last laugh: here’s jaw-dropping virtuosity for the soloist, sweeping melodies for the orchestra, and an audience favorite around the world.

- Antonín Dvořák Symphony No. 8

Dvořák’s pen might as well have been a paint brush. In his tuneful Eighth you can practically see autumn’s most vivid colors and the heart-melting glow of an October sunset.

Performed in Newark and Red Bank

Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No. 1

Opening Weekend | New Jersey Symphony Classical

Xian Zhang conductor

Joyce Yang piano

New Jersey Symphony

- Jessie Montgomery Hymn for Everyone

We launch the season with Montgomery’s open-arms musical welcome. In her Hymn for Everyone you’ll hear an echo of “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” often called the Black National Anthem.

- Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto No. 1

Slammed as a flop at its premiere, Tchaikovsky more than had the last laugh: here’s jaw-dropping virtuosity for the soloist, sweeping melodies for the orchestra, and an audience favorite around the world.

- Antonín Dvořák Symphony No. 8

Dvořák’s pen might as well have been a paint brush. In his tuneful Eighth you can practically see autumn’s most vivid colors and the heart-melting glow of an October sunset.

Performed in Newark and Red Bank

Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No. 1

Opening Weekend | New Jersey Symphony Classical

Xian Zhang conductor

Joyce Yang piano

New Jersey Symphony

- Jessie Montgomery Hymn for Everyone

We launch the season with Montgomery’s open-arms musical welcome. In her Hymn for Everyone you’ll hear an echo of “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” often called the Black National Anthem.

- Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto No. 1

Slammed as a flop at its premiere, Tchaikovsky more than had the last laugh: here’s jaw-dropping virtuosity for the soloist, sweeping melodies for the orchestra, and an audience favorite around the world.

- Antonín Dvořák Symphony No. 8

Dvořák’s pen might as well have been a paint brush. In his tuneful Eighth you can practically see autumn’s most vivid colors and the heart-melting glow of an October sunset.

Performed in Newark and Red Bank

Disney’s Fantasia in Concert

New Jersey Symphony at the Movies

Constantine Kitsopoulos conductor

New Jersey Symphony

Experience Disney’s groundbreaking marriage of symphonic music and animation, Fantasia. Beloved repertoire from the original 1940 version and Fantasia 2000, including The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, and The Nutcracker Suite, will be performed by the New Jersey Symphony while Disney’s stunning footage is shown on the big screen. Enjoy iconic moments and childhood favorites like never before!

Performed in Morristown, Red Bank and New Brunswick

Disney’s Fantasia in Concert

New Jersey Symphony at the Movies

Constantine Kitsopoulos conductor

New Jersey Symphony

Experience Disney’s groundbreaking marriage of symphonic music and animation, Fantasia. Beloved repertoire from the original 1940 version and Fantasia 2000, including The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, and The Nutcracker Suite, will be performed by the New Jersey Symphony while Disney’s stunning footage is shown on the big screen. Enjoy iconic moments and childhood favorites like never before!

Performed in Morristown, Red Bank and New Brunswick

Disney’s Fantasia in Concert

New Jersey Symphony at the Movies

Constantine Kitsopoulos conductor

New Jersey Symphony

Experience Disney’s groundbreaking marriage of symphonic music and animation, Fantasia. Beloved repertoire from the original 1940 version and Fantasia 2000, including The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, and The Nutcracker Suite, will be performed by the New Jersey Symphony while Disney’s stunning footage is shown on the big screen. Enjoy iconic moments and childhood favorites like never before!

Performed in Morristown, Red Bank and New Brunswick

Rhapsody in Blue

Plus works by Florence Price & Carlos Simon!

Tito Muñoz conductor

Michelle Cann piano

New Jersey Symphony

- Florence Price Piano Concerto in One Movement

An American genius, Florence Price mixes luscious lyricism with ragtime stomp. This recently unearthed gem won Cann—the leading interpreter of Price’s piano music—a 2023 GRAMMY.

- George Gershwin Rhapsody in Blue

United Airlines knows a good tune when it hears one, and that melody is the heartbeat of Gershwin’s classic. But not before the famous swooping clarinet solo gets this piece of the Roaring Twenties underway.

- Carlos Simon Zodiac (Northeast Premiere, New Jersey Symphony Co-Commission)

Carlos Simon is one of America’s leading contemporary composers, and in his latest music, a proud co-commission of the New Jersey Symphony, Simon gives voice to all 12 zodiac signs—the music at turns fiery, ethereal, and soaring.

- Aaron Copland Suite from Billy the Kid

Cowboy songs, folk tunes, and a visionary composer—all the ingredients that made Copland’s wild-west ballet a hit in the ‘30s and a favorite still.

Performed in Newark, Princeton and New Brunswick

Rhapsody in Blue

Plus works by Florence Price & Carlos Simon!

Tito Muñoz conductor

Michelle Cann piano

New Jersey Symphony

- Florence Price Piano Concerto in One Movement

An American genius, Florence Price mixes luscious lyricism with ragtime stomp. This recently unearthed gem won Cann—the leading interpreter of Price’s piano music—a 2023 GRAMMY.

- George Gershwin Rhapsody in Blue

United Airlines knows a good tune when it hears one, and that melody is the heartbeat of Gershwin’s classic. But not before the famous swooping clarinet solo gets this piece of the Roaring Twenties underway.

- Carlos Simon Zodiac (Northeast Premiere, New Jersey Symphony Co-Commission)

Carlos Simon is one of America’s leading contemporary composers, and in his latest music, a proud co-commission of the New Jersey Symphony, Simon gives voice to all 12 zodiac signs—the music at turns fiery, ethereal, and soaring.

- Aaron Copland Suite from Billy the Kid

Cowboy songs, folk tunes, and a visionary composer—all the ingredients that made Copland’s wild-west ballet a hit in the ‘30s and a favorite still.

Performed in Newark, Princeton and New Brunswick

Discover Rhapsody

in Blue

New Jersey Symphony Family Concert

Tito Muñoz conductor

Michelle Cann piano

New Jersey Symphony

Discover what makes a live orchestra concert so special. We’ll take a deep dive into one of the greatest American piano concertos, Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue, followed by Copland’s lively Suite from Billy the Kid.

Performed in Newark

Rhapsody in Blue

Plus works by Florence Price & Carlos Simon!

Tito Muñoz conductor

Michelle Cann piano

New Jersey Symphony

- Florence Price Piano Concerto in One Movement

An American genius, Florence Price mixes luscious lyricism with ragtime stomp. This recently unearthed gem won Cann—the leading interpreter of Price’s piano music—a 2023 GRAMMY.

- George Gershwin Rhapsody in Blue

United Airlines knows a good tune when it hears one, and that melody is the heartbeat of Gershwin’s classic. But not before the famous swooping clarinet solo gets this piece of the Roaring Twenties underway.

- Carlos Simon Zodiac (Northeast Premiere, New Jersey Symphony Co-Commission)

Carlos Simon is one of America’s leading contemporary composers, and in his latest music, a proud co-commission of the New Jersey Symphony, Simon gives voice to all 12 zodiac signs—the music at turns fiery, ethereal, and soaring.

- Aaron Copland Suite from Billy the Kid

Cowboy songs, folk tunes, and a visionary composer—all the ingredients that made Copland’s wild-west ballet a hit in the ‘30s and a favorite still.

Performed in Newark, Princeton and New Brunswick

Rhapsody in Blue

Plus works by Florence Price & Carlos Simon!

Tito Muñoz conductor

Michelle Cann piano

New Jersey Symphony

- Florence Price Piano Concerto in One Movement

An American genius, Florence Price mixes luscious lyricism with ragtime stomp. This recently unearthed gem won Cann—the leading interpreter of Price’s piano music—a 2023 GRAMMY.

- George Gershwin Rhapsody in Blue

United Airlines knows a good tune when it hears one, and that melody is the heartbeat of Gershwin’s classic. But not before the famous swooping clarinet solo gets this piece of the Roaring Twenties underway.

- Carlos Simon Zodiac (Northeast Premiere, New Jersey Symphony Co-Commission)

Carlos Simon is one of America’s leading contemporary composers, and in his latest music, a proud co-commission of the New Jersey Symphony, Simon gives voice to all 12 zodiac signs—the music at turns fiery, ethereal, and soaring.

- Aaron Copland Suite from Billy the Kid

Cowboy songs, folk tunes, and a visionary composer—all the ingredients that made Copland’s wild-west ballet a hit in the ‘30s and a favorite still.

Performed in Newark, Princeton and New Brunswick

Elf in Concert

New Jersey Symphony at the Movies

Conner Gray Covington conductor

New Jersey Symphony

Buddy was accidentally transported to the North Pole as a toddler and raised to adulthood among Santa’s elves. Unable to shake the feeling that he doesn’t fit in, the adult Buddy travels to New York, in full elf uniform, in search of his real father. This holiday season, relive this heartwarming holiday classic on a giant screen as every note of John Debney’s wonderful score is played live to picture in: Elf in Concert!

Performed in Newark and Red Bank

Elf in Concert

New Jersey Symphony at the Movies

Conner Gray Covington conductor

New Jersey Symphony

Buddy was accidentally transported to the North Pole as a toddler and raised to adulthood among Santa’s elves. Unable to shake the feeling that he doesn’t fit in, the adult Buddy travels to New York, in full elf uniform, in search of his real father. This holiday season, relive this heartwarming holiday classic on a giant screen as every note of John Debney’s wonderful score is played live to picture in: Elf in Concert!

Performed in Newark and Red Bank

Handel’s Messiah

New Jersey Symphony Holiday Tradition

Anthony Parnther conductor

Caitlin Gotimer soprano

Maria Dominique Lopez mezzo-soprano

Orson Van Gay II tenor

Shyheim Selvan Hinnant bass-baritone

Montclair State University Singers | Heather J. Buchanan, director

New Jersey Symphony

Handel’s Messiah embraces every emotion, from the first voice singing “Comfort ye,” inviting you to step aside from the season’s frenzy, to the riveting Amen Chorus at the end. In between are moments of transcendence, loss, and deeply-felt awe—what makes a classic a classic.

Performed in Princeton and Newark

Handel’s Messiah

New Jersey Symphony Holiday Tradition

Anthony Parnther conductor

Caitlin Gotimer soprano

Maria Dominique Lopez mezzo-soprano

Orson Van Gay II tenor

Shyheim Selvan Hinnant bass-baritone

Montclair State University Singers | Heather J. Buchanan, director

New Jersey Symphony

Handel’s Messiah embraces every emotion, from the first voice singing “Comfort ye,” inviting you to step aside from the season’s frenzy, to the riveting Amen Chorus at the end. In between are moments of transcendence, loss, and deeply-felt awe—what makes a classic a classic.

Performed in Princeton and Newark

Handel’s Messiah

New Jersey Symphony Holiday Tradition

Anthony Parnther conductor

Caitlin Gotimer soprano

Maria Dominique Lopez mezzo-soprano

Orson Van Gay II tenor

Shyheim Selvan Hinnant bass-baritone

Montclair State University Singers | Heather J. Buchanan, director

New Jersey Symphony

Handel’s Messiah embraces every emotion, from the first voice singing “Comfort ye,” inviting you to step aside from the season’s frenzy, to the riveting Amen Chorus at the end. In between are moments of transcendence, loss, and deeply-felt awe—what makes a classic a classic.

Performed in Princeton and Newark

Randall Goosby Returns

New Jersey Symphony Classical

Xian Zhang conductor

Randall Goosby violin

New Jersey Symphony

- Jean Sibelius Finlandia

Eight minutes that saved a nation. When Finland wrestled itself free from the Russian bear, Sibelius’ music was the Finns’ call to courage.

- Samuel Barber Violin Concerto

The most gorgeous violin concerto of the 20th century: the first two movements exquisitely touching, and the third a wild sprint for only the bravest of soloists.

- Pytor Ilyich Tchaikovsky Symphony No. 2, “Ukrainian”

Three Ukrainian folksongs were all Tchaikovsky needed for inspiration. From them, he spun his most joyful symphony.

Performed in New Brunswick, Princeton, Newark and Morristown

Randall Goosby Returns

New Jersey Symphony Classical

Xian Zhang conductor

Randall Goosby violin

New Jersey Symphony

- Jean Sibelius Finlandia

Eight minutes that saved a nation. When Finland wrestled itself free from the Russian bear, Sibelius’ music was the Finns’ call to courage.

- Samuel Barber Violin Concerto

The most gorgeous violin concerto of the 20th century: the first two movements exquisitely touching, and the third a wild sprint for only the bravest of soloists.

- Pytor Ilyich Tchaikovsky Symphony No. 2, “Ukrainian”

Three Ukrainian folksongs were all Tchaikovsky needed for inspiration. From them, he spun his most joyful symphony.

Performed in New Brunswick, Princeton, Newark and Morristown

Randall Goosby Returns

New Jersey Symphony Classical

Xian Zhang conductor

Randall Goosby violin

New Jersey Symphony

- Jean Sibelius Finlandia

Eight minutes that saved a nation. When Finland wrestled itself free from the Russian bear, Sibelius’ music was the Finns’ call to courage.

- Samuel Barber Violin Concerto

The most gorgeous violin concerto of the 20th century: the first two movements exquisitely touching, and the third a wild sprint for only the bravest of soloists.

- Pytor Ilyich Tchaikovsky Symphony No. 2, “Ukrainian”

Three Ukrainian folksongs were all Tchaikovsky needed for inspiration. From them, he spun his most joyful symphony.

Performed in New Brunswick, Princeton, Newark and Morristown

Randall Goosby Returns

New Jersey Symphony Classical

Xian Zhang conductor

Randall Goosby violin

New Jersey Symphony

- Jean Sibelius Finlandia

Eight minutes that saved a nation. When Finland wrestled itself free from the Russian bear, Sibelius’ music was the Finns’ call to courage.

- Samuel Barber Violin Concerto

The most gorgeous violin concerto of the 20th century: the first two movements exquisitely touching, and the third a wild sprint for only the bravest of soloists.

- Pytor Ilyich Tchaikovsky Symphony No. 2, “Ukrainian”

Three Ukrainian folksongs were all Tchaikovsky needed for inspiration. From them, he spun his most joyful symphony.

Performed in New Brunswick, Princeton, Newark and Morristown

Romeo & Juliet

Featuring The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey

Xian Zhang conductor

The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey

New Jersey Symphony

- Pytor Ilyich Tchaikovsky Romeo and Juliet Fantasy Overture

Tchaikovsky gives you all the passion and drama of Shakespeare’s two young lovers, as the New Jersey Symphony becomes a storyteller in real time.

- Sergei Prokofiev Selections from Romeo and Juliet

Considered too difficult, even undanceable at its unveiling, Prokofiev’s ballet with scene after scene of strikingly original music soon became the treasure of every ballet house the world over.

Performed in Newark and Red Bank

Romeo & Juliet

Featuring The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey

Xian Zhang conductor

The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey

New Jersey Symphony

- Pytor Ilyich Tchaikovsky Romeo and Juliet Fantasy Overture

Tchaikovsky gives you all the passion and drama of Shakespeare’s two young lovers, as the New Jersey Symphony becomes a storyteller in real time.

- Sergei Prokofiev Selections from Romeo and Juliet

Considered too difficult, even undanceable at its unveiling, Prokofiev’s ballet with scene after scene of strikingly original music soon became the treasure of every ballet house the world over.

Performed in Newark and Red Bank

Romeo & Juliet

Featuring The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey

Xian Zhang conductor

The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey

New Jersey Symphony

- Pytor Ilyich Tchaikovsky Romeo and Juliet Fantasy Overture

Tchaikovsky gives you all the passion and drama of Shakespeare’s two young lovers, as the New Jersey Symphony becomes a storyteller in real time.

- Sergei Prokofiev Selections from Romeo and Juliet

Considered too difficult, even undanceable at its unveiling, Prokofiev’s ballet with scene after scene of strikingly original music soon became the treasure of every ballet house the world over.

Performed in Newark and Red Bank

Romeo & Juliet

Featuring The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey

Xian Zhang conductor

The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey

New Jersey Symphony

- Pytor Ilyich Tchaikovsky Romeo and Juliet Fantasy Overture

Tchaikovsky gives you all the passion and drama of Shakespeare’s two young lovers, as the New Jersey Symphony becomes a storyteller in real time.

- Sergei Prokofiev Selections from Romeo and Juliet

Considered too difficult, even undanceable at its unveiling, Prokofiev’s ballet with scene after scene of strikingly original music soon became the treasure of every ballet house the world over.

Performed in Newark and Red Bank

2026 Lunar New Year Celebration

Celebration of the Year of the Horse

Sunny Xia conductor

Haochen Zhang piano

Peking University Alumni Chorus

New Jersey Symphony

Enjoy an evening of community and cultural exchange that is wonderful for families and children, as we celebrate the Year of the Horse. Seattle Symphony Associate Conductor Sunny Xia and Van Cliburn International Piano Competition Winner Haochen Zhang make their New Jersey Symphony debuts in this festive concert that celebrates music from East and West.

Performed in Newark

Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony

Time for Three Performs Contact

Markus Stenz conductor

Time for Three

Ranaan Meyer double bass | Nick Kendall violin | Charles Yang violin

New Jersey Symphony

- Richard Wagner Prelude to Act I of Lohengrin

It begins with the strings alone playing a whisperquiet passage of holy serenity. Soon the whole orchestra joins and builds in a full-throated cry. Wagner’s operatic stage is set for the arrival of the knight Lohengrin sent on a mission from God.

- Kevin Puts Contact

Time for Three, a self-described “classically trained garage band,” brings you the GRAMMY Award-winning concerto written for them by Pulitzer Prize-winning composer Kevin Puts. Created during the isolation of the early pandemic, Contact is “an expression of yearning for the fundamental need” of human connection.

- Ludwig van Beethoven Symphony No. 5

Four notes—dah, dah, dah, DAH—launched Beethoven’s Fifth in 1808 and have stamped all of western classical music since.

Performed in Morristown and Newark

Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony

Time for Three Performs Contact

Markus Stenz conductor

Time for Three

Ranaan Meyer double bass | Nick Kendall violin | Charles Yang violin

New Jersey Symphony

- Richard Wagner Prelude to Act I of Lohengrin

It begins with the strings alone playing a whisperquiet passage of holy serenity. Soon the whole orchestra joins and builds in a full-throated cry. Wagner’s operatic stage is set for the arrival of the knight Lohengrin sent on a mission from God.

- Kevin Puts Contact

Time for Three, a self-described “classically trained garage band,” brings you the GRAMMY Award-winning concerto written for them by Pulitzer Prize-winning composer Kevin Puts. Created during the isolation of the early pandemic, Contact is “an expression of yearning for the fundamental need” of human connection.

- Ludwig van Beethoven Symphony No. 5

Four notes—dah, dah, dah, DAH—launched Beethoven’s Fifth in 1808 and have stamped all of western classical music since.

Performed in Morristown and Newark

Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony

Time for Three Performs Contact

Markus Stenz conductor

Time for Three

Ranaan Meyer double bass | Nick Kendall violin | Charles Yang violin

New Jersey Symphony

- Richard Wagner Prelude to Act I of Lohengrin

It begins with the strings alone playing a whisperquiet passage of holy serenity. Soon the whole orchestra joins and builds in a full-throated cry. Wagner’s operatic stage is set for the arrival of the knight Lohengrin sent on a mission from God.

- Kevin Puts Contact

Time for Three, a self-described “classically trained garage band,” brings you the GRAMMY Award-winning concerto written for them by Pulitzer Prize-winning composer Kevin Puts. Created during the isolation of the early pandemic, Contact is “an expression of yearning for the fundamental need” of human connection.

- Ludwig van Beethoven Symphony No. 5

Four notes—dah, dah, dah, DAH—launched Beethoven’s Fifth in 1808 and have stamped all of western classical music since.

Performed in Morristown and Newark

Bartók’s Concerto

for Orchestra

New Jersey Symphony Classical

Ruth Reinhardt conductor

Eva Gevorgyan piano

New Jersey Symphony

- Béla Bartók Romanian Folk Dances

Informed by his numerous research trips across Hungary, this short and spry set of folk dances bursts with Transylvanian flavor and energy.

- Frédéric Chopin Piano Concerto No. 2

There are moments here that make time, and your breath, stand still. If ever you need evidence of the human spirit’s capacity for beauty, look to this remarkable creation of 20-year-old Chopin.

- Béla Bartók Concerto for Orchestra

Every section of the orchestra gets the spotlight to dazzling effect, and the Concerto’s last moments are some of the most thrilling in all classical music.

Performed in Newark, Princeton, Red Bank and New Brunswick

Bartók’s Concerto

for Orchestra

New Jersey Symphony Classical

Ruth Reinhardt conductor

Eva Gevorgyan piano

New Jersey Symphony

- Béla Bartók Romanian Folk Dances

Informed by his numerous research trips across Hungary, this short and spry set of folk dances bursts with Transylvanian flavor and energy.

- Frédéric Chopin Piano Concerto No. 2

There are moments here that make time, and your breath, stand still. If ever you need evidence of the human spirit’s capacity for beauty, look to this remarkable creation of 20-year-old Chopin.

- Béla Bartók Concerto for Orchestra

Every section of the orchestra gets the spotlight to dazzling effect, and the Concerto’s last moments are some of the most thrilling in all classical music.

Performed in Newark, Princeton, Red Bank and New Brunswick

Bartók’s Concerto

for Orchestra

New Jersey Symphony Classical

Ruth Reinhardt conductor

Eva Gevorgyan piano

New Jersey Symphony

- Béla Bartók Romanian Folk Dances

Informed by his numerous research trips across Hungary, this short and spry set of folk dances bursts with Transylvanian flavor and energy.

- Frédéric Chopin Piano Concerto No. 2

There are moments here that make time, and your breath, stand still. If ever you need evidence of the human spirit’s capacity for beauty, look to this remarkable creation of 20-year-old Chopin.

- Béla Bartók Concerto for Orchestra

Every section of the orchestra gets the spotlight to dazzling effect, and the Concerto’s last moments are some of the most thrilling in all classical music.

Performed in Newark, Princeton, Red Bank and New Brunswick

Bartók’s Concerto

for Orchestra

New Jersey Symphony Classical

Ruth Reinhardt conductor

Eva Gevorgyan piano

New Jersey Symphony

- Béla Bartók Romanian Folk Dances

Informed by his numerous research trips across Hungary, this short and spry set of folk dances bursts with Transylvanian flavor and energy.

- Frédéric Chopin Piano Concerto No. 2

There are moments here that make time, and your breath, stand still. If ever you need evidence of the human spirit’s capacity for beauty, look to this remarkable creation of 20-year-old Chopin.

- Béla Bartók Concerto for Orchestra

Every section of the orchestra gets the spotlight to dazzling effect, and the Concerto’s last moments are some of the most thrilling in all classical music.

Performed in Newark, Princeton, Red Bank and New Brunswick

Beethoven’s “Pastoral” Symphony

New Jersey Symphony Classical

Xian Zhang conductor

Juan Esteban Martinez clarinet

New Jersey Symphony

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Divertimento in D Major, K. 136

The spotlight opens on the New Jersey Symphony’s virtuoso strings playing the sunniest music Mozart ever created.

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Clarinet Concerto

Principal Clarinet Juan Esteban Martinez will shine in this sunny crown jewel of the clarinet repertoire, which was written for an earlier iteration of the modern clarinet.

- Ludwig van Beethoven Symphony No. 6, “Pastoral”

His greatest inspiration came from long walks in nature, score paper, and pencil stuffed in his pocket. Beethoven takes us with him in his Sixth, his music full of open-air melodies, and the drama of a ferocious storm.

Performed in Newark and Morristown

Discover Beethoven’s “Pastoral” Symphony

New Jersey Symphony Family Concert

Xian Zhang conductor

New Jersey Symphony

Discover the storytelling power of classical music! Beethoven’s “Pastoral” Symphony was one of his only works that depicts very specific scenes and storylines, which we’ll dive into measure by measure in this concert.

Performed in Newark

Beethoven’s “Pastoral” Symphony

New Jersey Symphony Classical

Xian Zhang conductor

Juan Esteban Martinez clarinet

New Jersey Symphony

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Divertimento in D Major, K. 136

The spotlight opens on the New Jersey Symphony’s virtuoso strings playing the sunniest music Mozart ever created.

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Clarinet Concerto

Principal Clarinet Juan Esteban Martinez will shine in this sunny crown jewel of the clarinet repertoire, which was written for an earlier iteration of the modern clarinet.

- Ludwig van Beethoven Symphony No. 6, “Pastoral”

His greatest inspiration came from long walks in nature, score paper, and pencil stuffed in his pocket. Beethoven takes us with him in his Sixth, his music full of open-air melodies, and the drama of a ferocious storm.

Performed in Newark and Morristown

Beethoven’s “Pastoral” Symphony

New Jersey Symphony Classical

Xian Zhang conductor

Juan Esteban Martinez clarinet

New Jersey Symphony

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Divertimento in D Major, K. 136

The spotlight opens on the New Jersey Symphony’s virtuoso strings playing the sunniest music Mozart ever created.

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Clarinet Concerto

Principal Clarinet Juan Esteban Martinez will shine in this sunny crown jewel of the clarinet repertoire, which was written for an earlier iteration of the modern clarinet.

- Ludwig van Beethoven Symphony No. 6, “Pastoral”

His greatest inspiration came from long walks in nature, score paper, and pencil stuffed in his pocket. Beethoven takes us with him in his Sixth, his music full of open-air melodies, and the drama of a ferocious storm.

Performed in Newark and Morristown

Xian Conducts

Prokofiev & Strauss

New Jersey Symphony Classical

Xian Zhang conductor

Francesca Dego violin

New Jersey Symphony

- Anton Webern Im Sommerwind

A lovingly lush hymn to the charms of summer, written just before Webern helped stand traditional classical music on its head.

- Sergei Prokofiev Violin Concerto No. 2

It opens with a wisp of melancholy Russian folksong and closes with castanets and Spanish flair, creating fireworks for a world-class violinist and orchestra.

- Richard Strauss Ein Heldenleben

Orchestras love this ode to “A Hero’s Life” for its bold, voluptuous sweep, created by Strauss as a musical pat on his own back.

Performed in Newark and Red Bank

Xian Conducts

Prokofiev & Strauss

New Jersey Symphony Classical

Xian Zhang conductor

Francesca Dego violin

New Jersey Symphony

- Anton Webern Im Sommerwind

A lovingly lush hymn to the charms of summer, written just before Webern helped stand traditional classical music on its head.

- Sergei Prokofiev Violin Concerto No. 2

It opens with a wisp of melancholy Russian folksong and closes with castanets and Spanish flair, creating fireworks for a world-class violinist and orchestra.

- Richard Strauss Ein Heldenleben

Orchestras love this ode to “A Hero’s Life” for its bold, voluptuous sweep, created by Strauss as a musical pat on his own back.

Performed in Newark and Red Bank

Xian Conducts

Prokofiev & Strauss

New Jersey Symphony Classical

Xian Zhang conductor

Francesca Dego violin

New Jersey Symphony

- Anton Webern Im Sommerwind

A lovingly lush hymn to the charms of summer, written just before Webern helped stand traditional classical music on its head.

- Sergei Prokofiev Violin Concerto No. 2

It opens with a wisp of melancholy Russian folksong and closes with castanets and Spanish flair, creating fireworks for a world-class violinist and orchestra.

- Richard Strauss Ein Heldenleben

Orchestras love this ode to “A Hero’s Life” for its bold, voluptuous sweep, created by Strauss as a musical pat on his own back.

Performed in Newark and Red Bank

Mozart’s Requiem

New Jersey Symphony Classical

Xian Zhang conductor

Mei Gui Zhang soprano

Taylor Raven mezzo-soprano

Eric Ferring tenor

Dashon Burton bass-baritone

Montclair State University Chorale | Heather J. Buchanan, director

New Jersey Symphony

- Gabriel Fauré Pavane

A slowly winding melody that started as a simple little five-minute piano solo. But when Fauré orchestrated his Pavane and added the rich sound of a chorus, he made magic and his greatest hit.

- Gustav Mahler Songs of a Wayfarer

Come enjoy one of the finest voices in America: bass-baritone Dashon Burton sings the suite of beautiful songs Mahler wrote as he took solace in nature after being spurned in love.

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Requiem

A swansong full of fire, grace, and a transcendent prayer that the human spirit will live on. Mozart’s Requiem was left maddeningly incomplete at his all-too-early death, but is nevertheless his final masterpiece.

Performed in Newark and New Brunswick

Mozart’s Requiem

New Jersey Symphony Classical

Xian Zhang conductor

Mei Gui Zhang soprano

Taylor Raven mezzo-soprano

Eric Ferring tenor

Dashon Burton bass-baritone

Montclair State University Chorale | Heather J. Buchanan, director

New Jersey Symphony

- Gabriel Fauré Pavane

A slowly winding melody that started as a simple little five-minute piano solo. But when Fauré orchestrated his Pavane and added the rich sound of a chorus, he made magic and his greatest hit.

- Gustav Mahler Songs of a Wayfarer

Come enjoy one of the finest voices in America: bass-baritone Dashon Burton sings the suite of beautiful songs Mahler wrote as he took solace in nature after being spurned in love.

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Requiem

A swansong full of fire, grace, and a transcendent prayer that the human spirit will live on. Mozart’s Requiem was left maddeningly incomplete at his all-too-early death, but is nevertheless his final masterpiece.

Performed in Newark and New Brunswick

Mozart’s Requiem

New Jersey Symphony Classical

Xian Zhang conductor

Mei Gui Zhang soprano

Taylor Raven mezzo-soprano

Eric Ferring tenor

Dashon Burton bass-baritone

Montclair State University Chorale | Heather J. Buchanan, director

New Jersey Symphony

- Gabriel Fauré Pavane

A slowly winding melody that started as a simple little five-minute piano solo. But when Fauré orchestrated his Pavane and added the rich sound of a chorus, he made magic and his greatest hit.

- Gustav Mahler Songs of a Wayfarer

Come enjoy one of the finest voices in America: bass-baritone Dashon Burton sings the suite of beautiful songs Mahler wrote as he took solace in nature after being spurned in love.

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Requiem

A swansong full of fire, grace, and a transcendent prayer that the human spirit will live on. Mozart’s Requiem was left maddeningly incomplete at his all-too-early death, but is nevertheless his final masterpiece.

Performed in Newark and New Brunswick

Joshua Bell Leads Mendelssohn’s “Italian”

New Jersey Symphony Classical

Joshua Bell conductor & violin

New Jersey Symphony

- Felix Mendelssohn The Hebrides (Fingal’s Cave)

The music swells and surges just as the waves off Scotland’s coast carried the young Mendelssohn past moody cliffs and caves and sent him reaching for his score paper.

- Édouard Lalo Symphonie espagnole

Though called a “symphony,” this is where superstar Joshua Bell stands and lets his Stradivarius violin sing the silvery songs of Spain.

- Felix Mendelssohn Symphony No. 4, “Italian”

“The jolliest piece I’ve ever done,” wrote an ecstatic young Mendelssohn to his parents back in Berlin, after arriving in Italy and falling in love with its sunshine, sidewalk tunes, coast, and effervescent colors—all of which he poured into his Fourth Symphony.

Performed in Newark, Princeton and Morristown

Joshua Bell Leads Mendelssohn’s “Italian”

New Jersey Symphony Classical

Joshua Bell conductor & violin

New Jersey Symphony

- Felix Mendelssohn The Hebrides (Fingal’s Cave)

The music swells and surges just as the waves off Scotland’s coast carried the young Mendelssohn past moody cliffs and caves and sent him reaching for his score paper.

- Édouard Lalo Symphonie espagnole

Though called a “symphony,” this is where superstar Joshua Bell stands and lets his Stradivarius violin sing the silvery songs of Spain.

- Felix Mendelssohn Symphony No. 4, “Italian”

“The jolliest piece I’ve ever done,” wrote an ecstatic young Mendelssohn to his parents back in Berlin, after arriving in Italy and falling in love with its sunshine, sidewalk tunes, coast, and effervescent colors—all of which he poured into his Fourth Symphony.

Performed in Newark, Princeton and Morristown

Joshua Bell Leads Mendelssohn’s “Italian”

New Jersey Symphony Classical

Joshua Bell conductor & violin

New Jersey Symphony

- Felix Mendelssohn The Hebrides (Fingal’s Cave)

The music swells and surges just as the waves off Scotland’s coast carried the young Mendelssohn past moody cliffs and caves and sent him reaching for his score paper.

- Édouard Lalo Symphonie espagnole

Though called a “symphony,” this is where superstar Joshua Bell stands and lets his Stradivarius violin sing the silvery songs of Spain.

- Felix Mendelssohn Symphony No. 4, “Italian”

“The jolliest piece I’ve ever done,” wrote an ecstatic young Mendelssohn to his parents back in Berlin, after arriving in Italy and falling in love with its sunshine, sidewalk tunes, coast, and effervescent colors—all of which he poured into his Fourth Symphony.

Performed in Newark, Princeton and Morristown

Joshua Bell Leads Mendelssohn’s “Italian”

New Jersey Symphony Classical

Joshua Bell conductor & violin

New Jersey Symphony

- Felix Mendelssohn The Hebrides (Fingal’s Cave)

The music swells and surges just as the waves off Scotland’s coast carried the young Mendelssohn past moody cliffs and caves and sent him reaching for his score paper.

- Édouard Lalo Symphonie espagnole

Though called a “symphony,” this is where superstar Joshua Bell stands and lets his Stradivarius violin sing the silvery songs of Spain.

- Felix Mendelssohn Symphony No. 4, “Italian”

“The jolliest piece I’ve ever done,” wrote an ecstatic young Mendelssohn to his parents back in Berlin, after arriving in Italy and falling in love with its sunshine, sidewalk tunes, coast, and effervescent colors—all of which he poured into his Fourth Symphony.

Performed in Newark, Princeton and Morristown

Star Wars: The Last Jedi in Concert

New Jersey Symphony at the Movies

Constantine Kitsopoulos conductor

New Jersey Symphony

Don’t miss this big-screen battle with the score performed live by the New Jersey Symphony. The Resistance is in desperate need of help when they find themselves impossibly pursued by the First Order. While Rey travels to a remote planet called Ahch-To to recruit Luke Skywalker to the Resistance, Finn and Rose, a mechanic, go on their own mission in the hopes of helping the Resistance finally escape the First Order. But everyone finds themselves on the salt-planet of Crait for a last stand.

Performed in Red Bank, Newark and New Brunswick

Star Wars: The Last Jedi in Concert

New Jersey Symphony at the Movies

Constantine Kitsopoulos conductor

New Jersey Symphony

Don’t miss this big-screen battle with the score performed live by the New Jersey Symphony. The Resistance is in desperate need of help when they find themselves impossibly pursued by the First Order. While Rey travels to a remote planet called Ahch-To to recruit Luke Skywalker to the Resistance, Finn and Rose, a mechanic, go on their own mission in the hopes of helping the Resistance finally escape the First Order. But everyone finds themselves on the salt-planet of Crait for a last stand.

Performed in Red Bank, Newark and New Brunswick

Star Wars: The Last Jedi in Concert

New Jersey Symphony at the Movies

Constantine Kitsopoulos conductor

New Jersey Symphony

Don’t miss this big-screen battle with the score performed live by the New Jersey Symphony. The Resistance is in desperate need of help when they find themselves impossibly pursued by the First Order. While Rey travels to a remote planet called Ahch-To to recruit Luke Skywalker to the Resistance, Finn and Rose, a mechanic, go on their own mission in the hopes of helping the Resistance finally escape the First Order. But everyone finds themselves on the salt-planet of Crait for a last stand.

Performed in Red Bank, Newark and New Brunswick

Symphonie fantastique

Season Finale | New Jersey Symphony Classical

Xian Zhang conductor

Emanuel Ax piano

New Jersey Symphony

- Allison Loggins-Hull New Work (World Premiere, New Jersey Symphony Commission)

You may have seen her performing with Lizzo at the GRAMMYs, or heard her on the soundtrack to The Lion King, or loved her Can You See? performed by the New Jersey Symphony last fall. Be the first to hear our Resident Artistic Partner’s latest creation.

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Mozart Piano Concerto No. 22

Mozart in his late 20s took a tune he wrote when he was eight and turned it into this half-hour masterpiece, the second of its three movements so moving that its first audience demanded a repeat.

- Hector Berlioz Symphonie fantastique

Smitten with unrequited love, Berlioz funneled all his frustrations and utter mind-blowing genius into a whirlwind of orchestral color.

Performed in New Brunswick, Princeton, Red Bank and Newark

Symphonie fantastique

Season Finale | New Jersey Symphony Classical

Xian Zhang conductor

Emanuel Ax piano

New Jersey Symphony

- Allison Loggins-Hull New Work (World Premiere, New Jersey Symphony Commission)

You may have seen her performing with Lizzo at the GRAMMYs, or heard her on the soundtrack to The Lion King, or loved her Can You See? performed by the New Jersey Symphony last fall. Be the first to hear our Resident Artistic Partner’s latest creation.

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Mozart Piano Concerto No. 22

Mozart in his late 20s took a tune he wrote when he was eight and turned it into this half-hour masterpiece, the second of its three movements so moving that its first audience demanded a repeat.

- Hector Berlioz Symphonie fantastique

Smitten with unrequited love, Berlioz funneled all his frustrations and utter mind-blowing genius into a whirlwind of orchestral color.

Performed in New Brunswick, Princeton, Red Bank and Newark

Symphonie fantastique

Season Finale | New Jersey Symphony Classical

Xian Zhang conductor

Emanuel Ax piano

New Jersey Symphony

- Allison Loggins-Hull New Work (World Premiere, New Jersey Symphony Commission)

You may have seen her performing with Lizzo at the GRAMMYs, or heard her on the soundtrack to The Lion King, or loved her Can You See? performed by the New Jersey Symphony last fall. Be the first to hear our Resident Artistic Partner’s latest creation.

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Mozart Piano Concerto No. 22

Mozart in his late 20s took a tune he wrote when he was eight and turned it into this half-hour masterpiece, the second of its three movements so moving that its first audience demanded a repeat.

- Hector Berlioz Symphonie fantastique

Smitten with unrequited love, Berlioz funneled all his frustrations and utter mind-blowing genius into a whirlwind of orchestral color.

Performed in New Brunswick, Princeton, Red Bank and Newark

Symphonie fantastique

Season Finale | New Jersey Symphony Classical

Xian Zhang conductor

Emanuel Ax piano

New Jersey Symphony

- Allison Loggins-Hull New Work (World Premiere, New Jersey Symphony Commission)

You may have seen her performing with Lizzo at the GRAMMYs, or heard her on the soundtrack to The Lion King, or loved her Can You See? performed by the New Jersey Symphony last fall. Be the first to hear our Resident Artistic Partner’s latest creation.

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Mozart Piano Concerto No. 22

Mozart in his late 20s took a tune he wrote when he was eight and turned it into this half-hour masterpiece, the second of its three movements so moving that its first audience demanded a repeat.

- Hector Berlioz Symphonie fantastique

Smitten with unrequited love, Berlioz funneled all his frustrations and utter mind-blowing genius into a whirlwind of orchestral color.

Performed in New Brunswick, Princeton, Red Bank and Newark

Ben Folds with the New Jersey Symphony

Ben Folds performs his greatest hits!

Ben Folds guest artist

New Jersey Symphony

Emmy-nominated singer-songwriter-composer Ben Folds joins the New Jersey Symphony for a unique and unforgettable performance of music from across his career. Widely regarded as one of the major musical influences of our generation, Folds’ enormous body of genre-bending music includes pop albums with Ben Folds Five, multiple solo albums, and numerous collaborative records. His latest album, 2023’s What Matters Most, is a blend of piano-driven pop rock songs, while his 2015 Concerto for Piano and Orchestra soared to #1 on both the Billboard classical and classical crossover charts. He released his first Christmas album in 2024 and last Fall recorded a live album slated for release in 2025 with the National Symphony Orchestra (NSO) at The Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C., where he served for eight years as the first artistic advisor to the NSO.

Performed in Newark and New Brunswick

Ben Folds with the New Jersey Symphony

Ben Folds performs his greatest hits!

Ben Folds guest artist

New Jersey Symphony

Emmy-nominated singer-songwriter-composer Ben Folds joins the New Jersey Symphony for a unique and unforgettable performance of music from across his career. Widely regarded as one of the major musical influences of our generation, Folds’ enormous body of genre-bending music includes pop albums with Ben Folds Five, multiple solo albums, and numerous collaborative records. His latest album, 2023’s What Matters Most, is a blend of piano-driven pop rock songs, while his 2015 Concerto for Piano and Orchestra soared to #1 on both the Billboard classical and classical crossover charts. He released his first Christmas album in 2024 and last Fall recorded a live album slated for release in 2025 with the National Symphony Orchestra (NSO) at The Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C., where he served for eight years as the first artistic advisor to the NSO.

Performed in Newark and New Brunswick

Program Notes | The Firebird with Xian Zhang