Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony with Xian Zhang

New Jersey Symphony Classical

Xian Zhang conductor

Gregory D. McDaniel conductor

Steven Banks saxophone

Felicia Moore soprano

Kelley O’Connor mezzo-soprano

Issachah Savage tenor

Reginald Smith Jr. baritone

Montclair State University Chorale | Heather J. Buchanan, director

New Jersey Symphony

- Pytor Ilyich Tchaikovsky Polonaise from Eugene Onegin

A lavish ball scene, the dashing hero and heroine twirling in splendor—a fun, festive dance lifted from Tchaikovsky’s opera.

- Billy Childs Diaspora

Inspired by Maya Angelou and other poets, Childs’ new concerto was written for the amazing Steven Banks, who says the music “follows the trajectory of the Black experience from Africa before slave trade to now, going forward in hope.”

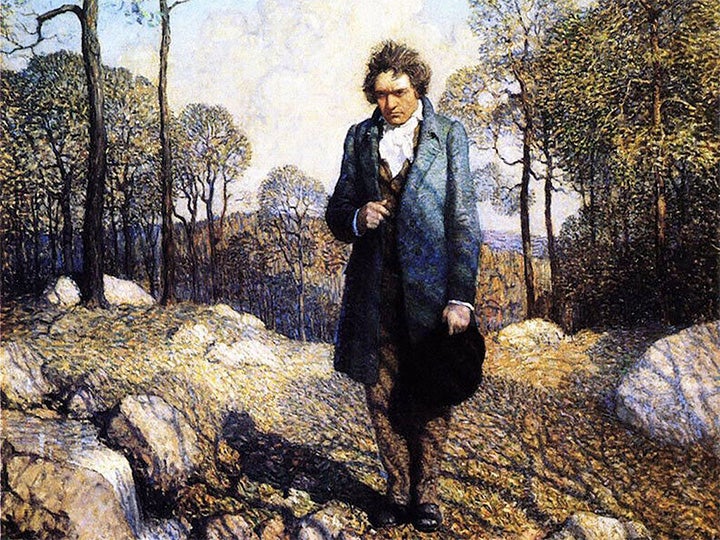

- Ludwig van Beethoven Symphony No. 9, “Choral”

The sheer volcanic power of Beethoven’s music makes the Ninth’s message soar. “Brotherhood! Joy!”—our world needs these clarion calls now more than ever.

Performed in Newark and New Brunswick

Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony with Xian Zhang

New Jersey Symphony Classical

Xian Zhang conductor

Gregory D. McDaniel conductor

Steven Banks saxophone

Felicia Moore soprano

Kelley O’Connor mezzo-soprano

Issachah Savage tenor

Reginald Smith Jr. baritone

Montclair State University Chorale | Heather J. Buchanan, director

New Jersey Symphony

- Pytor Ilyich Tchaikovsky Polonaise from Eugene Onegin

A lavish ball scene, the dashing hero and heroine twirling in splendor—a fun, festive dance lifted from Tchaikovsky’s opera.

- Billy Childs Diaspora

Inspired by Maya Angelou and other poets, Childs’ new concerto was written for the amazing Steven Banks, who says the music “follows the trajectory of the Black experience from Africa before slave trade to now, going forward in hope.”

- Ludwig van Beethoven Symphony No. 9, “Choral”

The sheer volcanic power of Beethoven’s music makes the Ninth’s message soar. “Brotherhood! Joy!”—our world needs these clarion calls now more than ever.

Performed in Newark and New Brunswick

Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony with Xian Zhang

New Jersey Symphony Classical

Xian Zhang conductor

Gregory D. McDaniel conductor

Steven Banks saxophone

Felicia Moore soprano

Kelley O’Connor mezzo-soprano

Issachah Savage tenor

Reginald Smith Jr. baritone

Montclair State University Chorale | Heather J. Buchanan, director

New Jersey Symphony

- Pytor Ilyich Tchaikovsky Polonaise from Eugene Onegin

A lavish ball scene, the dashing hero and heroine twirling in splendor—a fun, festive dance lifted from Tchaikovsky’s opera.

- Billy Childs Diaspora

Inspired by Maya Angelou and other poets, Childs’ new concerto was written for the amazing Steven Banks, who says the music “follows the trajectory of the Black experience from Africa before slave trade to now, going forward in hope.”

- Ludwig van Beethoven Symphony No. 9, “Choral”

The sheer volcanic power of Beethoven’s music makes the Ninth’s message soar. “Brotherhood! Joy!”—our world needs these clarion calls now more than ever.

Performed in Newark and New Brunswick

Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony with Xian Zhang

New Jersey Symphony Classical

Xian Zhang conductor

Gregory D. McDaniel conductor

Steven Banks saxophone

Felicia Moore soprano

Kelley O’Connor mezzo-soprano

Issachah Savage tenor

Reginald Smith Jr. baritone

Montclair State University Chorale | Heather J. Buchanan, director

New Jersey Symphony

- Pytor Ilyich Tchaikovsky Polonaise from Eugene Onegin

A lavish ball scene, the dashing hero and heroine twirling in splendor—a fun, festive dance lifted from Tchaikovsky’s opera.

- Billy Childs Diaspora

Inspired by Maya Angelou and other poets, Childs’ new concerto was written for the amazing Steven Banks, who says the music “follows the trajectory of the Black experience from Africa before slave trade to now, going forward in hope.”

- Ludwig van Beethoven Symphony No. 9, “Choral”

The sheer volcanic power of Beethoven’s music makes the Ninth’s message soar. “Brotherhood! Joy!”—our world needs these clarion calls now more than ever.

Performed in Newark and New Brunswick

Star Wars: The Force Awakens in Concert

New Jersey Symphony at the Movies

Constantine Kitsopoulos conductor

New Jersey Symphony

Thirty years after the defeat of the Empire, Luke Skywalker has vanished, and a new threat has risen: The First Order, led by the mysterious Supreme Leader Snoke and his enforcer, Kylo Ren. General Leia Organa’s military force, the Resistance—and unlikely heroes brought together by fate—are the galaxy’s only hope. Experience the complete film with the New Jersey Symphony performing John Williams’ thrilling score live.

Performed in Red Bank, Morristown, Newark and New Brunswick

Star Wars: The Force Awakens in Concert

New Jersey Symphony at the Movies

Constantine Kitsopoulos conductor

New Jersey Symphony

Thirty years after the defeat of the Empire, Luke Skywalker has vanished, and a new threat has risen: The First Order, led by the mysterious Supreme Leader Snoke and his enforcer, Kylo Ren. General Leia Organa’s military force, the Resistance—and unlikely heroes brought together by fate—are the galaxy’s only hope. Experience the complete film with the New Jersey Symphony performing John Williams’ thrilling score live.

Performed in Red Bank, Morristown, Newark and New Brunswick

Star Wars: The Force Awakens in Concert

New Jersey Symphony at the Movies

Constantine Kitsopoulos conductor

New Jersey Symphony

Thirty years after the defeat of the Empire, Luke Skywalker has vanished, and a new threat has risen: The First Order, led by the mysterious Supreme Leader Snoke and his enforcer, Kylo Ren. General Leia Organa’s military force, the Resistance—and unlikely heroes brought together by fate—are the galaxy’s only hope. Experience the complete film with the New Jersey Symphony performing John Williams’ thrilling score live.

Performed in Red Bank, Morristown, Newark and New Brunswick

Star Wars: The Force Awakens in Concert

New Jersey Symphony at the Movies

Constantine Kitsopoulos conductor

New Jersey Symphony

Thirty years after the defeat of the Empire, Luke Skywalker has vanished, and a new threat has risen: The First Order, led by the mysterious Supreme Leader Snoke and his enforcer, Kylo Ren. General Leia Organa’s military force, the Resistance—and unlikely heroes brought together by fate—are the galaxy’s only hope. Experience the complete film with the New Jersey Symphony performing John Williams’ thrilling score live.

Performed in Red Bank, Morristown, Newark and New Brunswick

Youth Orchestra Spring Concert

Two performances in one day! | Youth Orchestra Showcase

Diego García artistic director, The Anna P. Drago Chair

Terrence Thornhill associate conductor & curriculum specialist

New Jersey Symphony Youth Orchestra, The Resident Youth Orchestra of the John J. Cali School of Music at Montclair State University

The New Jersey Symphony Youth Orchestra will showcase 300 talented young musicians across two performances as part of their annual Spring Concert on Sunday, April 27 in Newark. Experience vibrant performances and celebrate the achievements of the 2024–25 season, including a special tribute to the graduating seniors.

Performed in Newark

Youth Orchestra Spring Concert

Two performances in one day! | Youth Orchestra Showcase

Diego García artistic director, The Anna P. Drago Chair

Terrence Thornhill associate conductor & curriculum specialist

New Jersey Symphony Youth Orchestra, The Resident Youth Orchestra of the John J. Cali School of Music at Montclair State University

The New Jersey Symphony Youth Orchestra will showcase 300 talented young musicians across two performances as part of their annual Spring Concert on Sunday, April 27 in Newark. Experience vibrant performances and celebrate the achievements of the 2024–25 season, including a special tribute to the graduating seniors.

Performed in Newark

Haydn’s Creation

New Jersey Symphony at the Cathedral

John J. Miller conductor

Lorraine Ernest soprano

Theodore Chletsos tenor

Jorge Ocasio bass-baritone

The Archdiocesan Festival Choir

The Cathedral Choir

New Jersey Symphony

The Cathedral Basilica of the Sacred Heart in Newark, NJ invites all to experience the music of Franz Joseph Haydn’s The Creation, featuring The Archdiocesan Festival Choir, The Cathedral Choir, vocal soloists and the New Jersey Symphony with John J. Miller conducting.

Performed in Newark

The Music of Led Zeppelin

Featuring hits like “Kashmir,” “Black Dog,” “Stairway to Heaven” and more!

Brent Havens conductor & arranger

Windborne Music Group

Justin Sargent vocalist

New Jersey Symphony

The New Jersey Symphony and Windborne Music Group bridge the gulf between classical music and rock n’ roll to present The Music of Led Zeppelin, celebrating the best of the legendary classic rock group. Amplified with full-on guitars and screaming vocals, sing and dance along as Led Zeppelin’s “sheer blast and power” is put on full display riff for riff with new musical colors. Timeless hits like “Kashmir,” “Black Dog,” “Stairway to Heaven” and more will get you on your feet in this special concert you don’t want to miss!

Performed in Englewood and New Brunswick

The Music of Led Zeppelin

Featuring hits like “Kashmir,” “Black Dog,” “Stairway to Heaven” and more!

Brent Havens conductor & arranger

Windborne Music Group

Justin Sargent vocalist

New Jersey Symphony

The New Jersey Symphony and Windborne Music Group bridge the gulf between classical music and rock n’ roll to present The Music of Led Zeppelin, celebrating the best of the legendary classic rock group. Amplified with full-on guitars and screaming vocals, sing and dance along as Led Zeppelin’s “sheer blast and power” is put on full display riff for riff with new musical colors. Timeless hits like “Kashmir,” “Black Dog,” “Stairway to Heaven” and more will get you on your feet in this special concert you don’t want to miss!

Performed in Englewood and New Brunswick

Xian Conducts Mozart

New Jersey Symphony musicians take the spotlight!

Xian Zhang conductor

Eric Wyrick violin

Francine Storck violin

New Jersey Symphony

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Eine kleine Nachtmusik

Mozart may have tossed this off for a Viennese party one evening, but there is no piece more charming and beguiling than his “a little night music.”

- Johann Sebastian Bach Double Concerto for Two Violins

The spotlight’s on our two superstar principal violins, Eric Wyrick and Francine Storck, in perhaps the most beautiful duet ever created.

- Michael Abels Delights and Dances

Delight in this imaginative, bluesy work for solo string quartet and string orchestra, with New Jersey Symphony’s own musicians taking the spotlight in a series of captivating solos.

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony No. 35, “Haffner”

Mozart had intended to jot down a little occasional piece, but brilliant music kept pouring out of his pen until he’d made a dazzling full-fledged symphony, one of his best.

Performed in Princeton and Newark

Discover Mozart & Bach

New Jersey Symphony Family Concert:

A Music Discovery Zone

Xian Zhang conductor

Gregory D. McDaniel conductor

Bill Barclay host

Eric Wyrick violin

Francine Storck violin

Annamaria Witek cello

New Jersey Symphony

Discover what makes a live orchestra concert so special. We’ll take a deep dive into works by Mozart, as well as J.S. Bach’s incredibly famous Double Concerto for Two Violins. Also featured on the program is 2024 Henry Lewis Concerto Competition winner, cellist Annamaria Witek. Inspired by Leonard Bernstein’s masterful way of putting young audiences at the center of music-making, this interactive concert will feature inside tips, listening cues and fun facts that make for the perfect Saturday afternoon family outing!

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Selection from Eine kleine Nachtmusik

- Camille Saint-Saëns Selection from Cello Concerto No. 1

- Johann Sebastian Bach Double Concerto for Two Violins

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony No. 35, “Haffner”

Performed in Newark

Xian Conducts Mozart

New Jersey Symphony musicians take the spotlight!

Xian Zhang conductor

Eric Wyrick violin

Francine Storck violin

New Jersey Symphony

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Eine kleine Nachtmusik

Mozart may have tossed this off for a Viennese party one evening, but there is no piece more charming and beguiling than his “a little night music.”

- Johann Sebastian Bach Double Concerto for Two Violins

The spotlight’s on our two superstar principal violins, Eric Wyrick and Francine Storck, in perhaps the most beautiful duet ever created.

- Michael Abels Delights and Dances

Delight in this imaginative, bluesy work for solo string quartet and string orchestra, with New Jersey Symphony’s own musicians taking the spotlight in a series of captivating solos.

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony No. 35, “Haffner”

Mozart had intended to jot down a little occasional piece, but brilliant music kept pouring out of his pen until he’d made a dazzling full-fledged symphony, one of his best.

Performed in Princeton and Newark

Xian Conducts Mozart

New Jersey Symphony musicians take the spotlight!

Xian Zhang conductor

Eric Wyrick violin

Francine Storck violin

New Jersey Symphony

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Eine kleine Nachtmusik

Mozart may have tossed this off for a Viennese party one evening, but there is no piece more charming and beguiling than his “a little night music.”

- Johann Sebastian Bach Double Concerto for Two Violins

The spotlight’s on our two superstar principal violins, Eric Wyrick and Francine Storck, in perhaps the most beautiful duet ever created.

- Michael Abels Delights and Dances

Delight in this imaginative, bluesy work for solo string quartet and string orchestra, with New Jersey Symphony’s own musicians taking the spotlight in a series of captivating solos.

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony No. 35, “Haffner”

Mozart had intended to jot down a little occasional piece, but brilliant music kept pouring out of his pen until he’d made a dazzling full-fledged symphony, one of his best.

Performed in Princeton and Newark

2025 Spring into Music Gala & Auction

Gala Reception and Dinner, Concert and Auction

Join the New Jersey Symphony and an array of cultural, social, business and civic leaders for an unforgettable evening of fine dining and entertainment as we honor former Governor Thomas H. Kean and his dedication to the performing arts industry in New Jersey. The event will feature a lavish cocktail reception with a few dazzling surprises, a dinner with a private performance featuring members of the New Jersey Symphony and students of the New Jersey Symphony Youth Orchestra and a silent auction.

Presented in West Orange

Rachmaninoff and Shostakovich

Season Finale | New Jersey Symphony Classical

Xian Zhang conductor

Conrad Tao piano

New Jersey Symphony

- Sergei Rachmaninoff Piano Concerto No. 2

No piece has introduced and won more people to classical music than Rachmaninoff’s magnificent work for piano and orchestra.

- Dmitri Shostakovich Symphony No. 5

When Shostakovich’s Fifth received a half-hour standing ovation at its premiere, the world knew that a classic was born—and it remains a landmark work for the virtuoso orchestra.

Performed in Morristown, Princeton, Red Bank and Newark

Rachmaninoff and Shostakovich

Season Finale | New Jersey Symphony Classical

Xian Zhang conductor

Conrad Tao piano

New Jersey Symphony

- Sergei Rachmaninoff Piano Concerto No. 2

No piece has introduced and won more people to classical music than Rachmaninoff’s magnificent work for piano and orchestra.

- Dmitri Shostakovich Symphony No. 5

When Shostakovich’s Fifth received a half-hour standing ovation at its premiere, the world knew that a classic was born—and it remains a landmark work for the virtuoso orchestra.

Performed in Morristown, Princeton, Red Bank and Newark

Rachmaninoff and Shostakovich

Season Finale | New Jersey Symphony Classical

Xian Zhang conductor

Conrad Tao piano

New Jersey Symphony

- Sergei Rachmaninoff Piano Concerto No. 2

No piece has introduced and won more people to classical music than Rachmaninoff’s magnificent work for piano and orchestra.

- Dmitri Shostakovich Symphony No. 5

When Shostakovich’s Fifth received a half-hour standing ovation at its premiere, the world knew that a classic was born—and it remains a landmark work for the virtuoso orchestra.

Performed in Morristown, Princeton, Red Bank and Newark

Rachmaninoff and Shostakovich

Season Finale | New Jersey Symphony Classical

Xian Zhang conductor

Conrad Tao piano

New Jersey Symphony

- Sergei Rachmaninoff Piano Concerto No. 2

No piece has introduced and won more people to classical music than Rachmaninoff’s magnificent work for piano and orchestra.

- Dmitri Shostakovich Symphony No. 5

When Shostakovich’s Fifth received a half-hour standing ovation at its premiere, the world knew that a classic was born—and it remains a landmark work for the virtuoso orchestra.

Performed in Morristown, Princeton, Red Bank and Newark

How to Train Your Dragon in Concert

New Jersey Symphony at the Movies

Lawrence Loh conductor

New Jersey Symphony

DreamWorks’ How to Train Your Dragon is a captivating and original story about a young Viking named Hiccup, who defies tradition when he befriends one of his deadliest foes—a ferocious dragon he calls Toothless. Together, these unlikely heroes must fight against all odds to save both their worlds. Featuring John Powell’s Oscar-nominated score performed live to picture, How to Train Your Dragon in Concert is a thrilling experience for all ages.

Performed in Morristown, New Brunswick and Newark

How to Train Your Dragon in Concert

New Jersey Symphony at the Movies

Lawrence Loh conductor

New Jersey Symphony

DreamWorks’ How to Train Your Dragon is a captivating and original story about a young Viking named Hiccup, who defies tradition when he befriends one of his deadliest foes—a ferocious dragon he calls Toothless. Together, these unlikely heroes must fight against all odds to save both their worlds. Featuring John Powell’s Oscar-nominated score performed live to picture, How to Train Your Dragon in Concert is a thrilling experience for all ages.

Performed in Morristown, New Brunswick and Newark

How to Train Your Dragon in Concert

New Jersey Symphony at the Movies

Lawrence Loh conductor

New Jersey Symphony

DreamWorks’ How to Train Your Dragon is a captivating and original story about a young Viking named Hiccup, who defies tradition when he befriends one of his deadliest foes—a ferocious dragon he calls Toothless. Together, these unlikely heroes must fight against all odds to save both their worlds. Featuring John Powell’s Oscar-nominated score performed live to picture, How to Train Your Dragon in Concert is a thrilling experience for all ages.

Performed in Morristown, New Brunswick and Newark

TwoSet Violin with the New Jersey Symphony

Part of the TwoSet Violin World Tour

TwoSet Violin

New Jersey Symphony

World-famous YouTube classical music comedy duo TwoSet Violin take the stage with the New Jersey Symphony for a wide-ranging night of musical fun! Violinists Eddy Chen and Brett Yang will take their unique brand of earnest and silly musical comedy to a new level in this performance, with the backing of a full symphony orchestra.

Performed in Newark

Opening Night Celebration

Dinner Prelude, Concert and After-Party

You are invited to the New Jersey Symphony’s 2025 Season Opening Celebration honoring Xian Zhang’s 10th season as Music Director. Guests will enjoy an elegant dinner prelude, the season opening concert featuring Music Director Xian Zhang, guest artist Joyce Yang and the New Jersey Symphony and a dessert after-party.

Presented in Newark

Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No. 1

Opening Weekend | New Jersey Symphony Classical

Xian Zhang conductor

Joyce Yang piano

New Jersey Symphony

- Jessie Montgomery Hymn for Everyone

We launch the season with Montgomery’s open-arms musical welcome. In her Hymn for Everyone you’ll hear an echo of “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” often called the Black National Anthem.

- Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto No. 1

Slammed as a flop at its premiere, Tchaikovsky more than had the last laugh: here’s jaw-dropping virtuosity for the soloist, sweeping melodies for the orchestra, and an audience favorite around the world.

- Antonín Dvořák Symphony No. 8

Dvořák’s pen might as well have been a paint brush. In his tuneful Eighth you can practically see autumn’s most vivid colors and the heart-melting glow of an October sunset.

Performed in Newark and Red Bank

Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No. 1

Opening Weekend | New Jersey Symphony Classical

Xian Zhang conductor

Joyce Yang piano

New Jersey Symphony

- Jessie Montgomery Hymn for Everyone

We launch the season with Montgomery’s open-arms musical welcome. In her Hymn for Everyone you’ll hear an echo of “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” often called the Black National Anthem.

- Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto No. 1

Slammed as a flop at its premiere, Tchaikovsky more than had the last laugh: here’s jaw-dropping virtuosity for the soloist, sweeping melodies for the orchestra, and an audience favorite around the world.

- Antonín Dvořák Symphony No. 8

Dvořák’s pen might as well have been a paint brush. In his tuneful Eighth you can practically see autumn’s most vivid colors and the heart-melting glow of an October sunset.

Performed in Newark and Red Bank

Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No. 1

Opening Weekend | New Jersey Symphony Classical

Xian Zhang conductor

Joyce Yang piano

New Jersey Symphony

- Jessie Montgomery Hymn for Everyone

We launch the season with Montgomery’s open-arms musical welcome. In her Hymn for Everyone you’ll hear an echo of “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” often called the Black National Anthem.

- Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto No. 1

Slammed as a flop at its premiere, Tchaikovsky more than had the last laugh: here’s jaw-dropping virtuosity for the soloist, sweeping melodies for the orchestra, and an audience favorite around the world.

- Antonín Dvořák Symphony No. 8

Dvořák’s pen might as well have been a paint brush. In his tuneful Eighth you can practically see autumn’s most vivid colors and the heart-melting glow of an October sunset.

Performed in Newark and Red Bank

Disney’s Fantasia in Concert

New Jersey Symphony at the Movies

Constantine Kitsopoulos conductor

New Jersey Symphony

Experience Disney’s groundbreaking marriage of symphonic music and animation, Fantasia. Beloved repertoire from the original 1940 version and Fantasia 2000, including The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, and The Nutcracker Suite, will be performed by the New Jersey Symphony while Disney’s stunning footage is shown on the big screen. Enjoy iconic moments and childhood favorites like never before!

Performed in Morristown, Red Bank and New Brunswick

Disney’s Fantasia in Concert

New Jersey Symphony at the Movies

Constantine Kitsopoulos conductor

New Jersey Symphony

Experience Disney’s groundbreaking marriage of symphonic music and animation, Fantasia. Beloved repertoire from the original 1940 version and Fantasia 2000, including The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, and The Nutcracker Suite, will be performed by the New Jersey Symphony while Disney’s stunning footage is shown on the big screen. Enjoy iconic moments and childhood favorites like never before!

Performed in Morristown, Red Bank and New Brunswick

Disney’s Fantasia in Concert

New Jersey Symphony at the Movies

Constantine Kitsopoulos conductor

New Jersey Symphony

Experience Disney’s groundbreaking marriage of symphonic music and animation, Fantasia. Beloved repertoire from the original 1940 version and Fantasia 2000, including The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, and The Nutcracker Suite, will be performed by the New Jersey Symphony while Disney’s stunning footage is shown on the big screen. Enjoy iconic moments and childhood favorites like never before!

Performed in Morristown, Red Bank and New Brunswick

Rhapsody in Blue

Plus works by Florence Price & Carlos Simon!

Tito Muñoz conductor

Michelle Cann piano

New Jersey Symphony

- Florence Price Piano Concerto in One Movement

An American genius, Florence Price mixes luscious lyricism with ragtime stomp. This recently unearthed gem won Cann—the leading interpreter of Price’s piano music—a 2023 GRAMMY.

- George Gershwin Rhapsody in Blue

United Airlines knows a good tune when it hears one, and that melody is the heartbeat of Gershwin’s classic. But not before the famous swooping clarinet solo gets this piece of the Roaring Twenties underway.

- Carlos Simon Zodiac (Northeast Premiere, New Jersey Symphony Co-Commission)

Carlos Simon is one of America’s leading contemporary composers, and in his latest music, a proud co-commission of the New Jersey Symphony, Simon gives voice to all 12 zodiac signs—the music at turns fiery, ethereal, and soaring.

- Aaron Copland Suite from Billy the Kid

Cowboy songs, folk tunes, and a visionary composer—all the ingredients that made Copland’s wild-west ballet a hit in the ‘30s and a favorite still.

Performed in Newark, Princeton and New Brunswick

Rhapsody in Blue

Plus works by Florence Price & Carlos Simon!

Tito Muñoz conductor

Michelle Cann piano

New Jersey Symphony

- Florence Price Piano Concerto in One Movement

An American genius, Florence Price mixes luscious lyricism with ragtime stomp. This recently unearthed gem won Cann—the leading interpreter of Price’s piano music—a 2023 GRAMMY.

- George Gershwin Rhapsody in Blue

United Airlines knows a good tune when it hears one, and that melody is the heartbeat of Gershwin’s classic. But not before the famous swooping clarinet solo gets this piece of the Roaring Twenties underway.

- Carlos Simon Zodiac (Northeast Premiere, New Jersey Symphony Co-Commission)

Carlos Simon is one of America’s leading contemporary composers, and in his latest music, a proud co-commission of the New Jersey Symphony, Simon gives voice to all 12 zodiac signs—the music at turns fiery, ethereal, and soaring.

- Aaron Copland Suite from Billy the Kid

Cowboy songs, folk tunes, and a visionary composer—all the ingredients that made Copland’s wild-west ballet a hit in the ‘30s and a favorite still.

Performed in Newark, Princeton and New Brunswick

Discover Rhapsody

in Blue

New Jersey Symphony Family Concert

Tito Muñoz conductor

Michelle Cann piano

New Jersey Symphony

Discover what makes a live orchestra concert so special. We’ll take a deep dive into one of the greatest American piano concertos, Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue, followed by Copland’s lively Suite from Billy the Kid.

Performed in Newark

Rhapsody in Blue

Plus works by Florence Price & Carlos Simon!

Tito Muñoz conductor

Michelle Cann piano

New Jersey Symphony

- Florence Price Piano Concerto in One Movement

An American genius, Florence Price mixes luscious lyricism with ragtime stomp. This recently unearthed gem won Cann—the leading interpreter of Price’s piano music—a 2023 GRAMMY.

- George Gershwin Rhapsody in Blue

United Airlines knows a good tune when it hears one, and that melody is the heartbeat of Gershwin’s classic. But not before the famous swooping clarinet solo gets this piece of the Roaring Twenties underway.

- Carlos Simon Zodiac (Northeast Premiere, New Jersey Symphony Co-Commission)

Carlos Simon is one of America’s leading contemporary composers, and in his latest music, a proud co-commission of the New Jersey Symphony, Simon gives voice to all 12 zodiac signs—the music at turns fiery, ethereal, and soaring.

- Aaron Copland Suite from Billy the Kid

Cowboy songs, folk tunes, and a visionary composer—all the ingredients that made Copland’s wild-west ballet a hit in the ‘30s and a favorite still.

Performed in Newark, Princeton and New Brunswick

Rhapsody in Blue

Plus works by Florence Price & Carlos Simon!

Tito Muñoz conductor

Michelle Cann piano

New Jersey Symphony

- Florence Price Piano Concerto in One Movement

An American genius, Florence Price mixes luscious lyricism with ragtime stomp. This recently unearthed gem won Cann—the leading interpreter of Price’s piano music—a 2023 GRAMMY.

- George Gershwin Rhapsody in Blue

United Airlines knows a good tune when it hears one, and that melody is the heartbeat of Gershwin’s classic. But not before the famous swooping clarinet solo gets this piece of the Roaring Twenties underway.

- Carlos Simon Zodiac (Northeast Premiere, New Jersey Symphony Co-Commission)

Carlos Simon is one of America’s leading contemporary composers, and in his latest music, a proud co-commission of the New Jersey Symphony, Simon gives voice to all 12 zodiac signs—the music at turns fiery, ethereal, and soaring.

- Aaron Copland Suite from Billy the Kid

Cowboy songs, folk tunes, and a visionary composer—all the ingredients that made Copland’s wild-west ballet a hit in the ‘30s and a favorite still.

Performed in Newark, Princeton and New Brunswick

Elf in Concert

New Jersey Symphony at the Movies

Conner Gray Covington conductor

New Jersey Symphony

Buddy was accidentally transported to the North Pole as a toddler and raised to adulthood among Santa’s elves. Unable to shake the feeling that he doesn’t fit in, the adult Buddy travels to New York, in full elf uniform, in search of his real father. This holiday season, relive this heartwarming holiday classic on a giant screen as every note of John Debney’s wonderful score is played live to picture in: Elf in Concert!

Performed in Newark and Red Bank

Elf in Concert

New Jersey Symphony at the Movies

Conner Gray Covington conductor

New Jersey Symphony

Buddy was accidentally transported to the North Pole as a toddler and raised to adulthood among Santa’s elves. Unable to shake the feeling that he doesn’t fit in, the adult Buddy travels to New York, in full elf uniform, in search of his real father. This holiday season, relive this heartwarming holiday classic on a giant screen as every note of John Debney’s wonderful score is played live to picture in: Elf in Concert!

Performed in Newark and Red Bank

Handel’s Messiah

New Jersey Symphony Holiday Tradition

Anthony Parnther conductor

Caitlin Gotimer soprano

Maria Dominique Lopez mezzo-soprano

Orson Van Gay II tenor

Shyheim Selvan Hinnant bass-baritone

Montclair State University Singers | Heather J. Buchanan, director

New Jersey Symphony

Handel’s Messiah embraces every emotion, from the first voice singing “Comfort ye,” inviting you to step aside from the season’s frenzy, to the riveting Amen Chorus at the end. In between are moments of transcendence, loss, and deeply-felt awe—what makes a classic a classic.

Performed in Princeton and Newark

Handel’s Messiah

New Jersey Symphony Holiday Tradition

Anthony Parnther conductor

Caitlin Gotimer soprano

Maria Dominique Lopez mezzo-soprano

Orson Van Gay II tenor

Shyheim Selvan Hinnant bass-baritone

Montclair State University Singers | Heather J. Buchanan, director

New Jersey Symphony

Handel’s Messiah embraces every emotion, from the first voice singing “Comfort ye,” inviting you to step aside from the season’s frenzy, to the riveting Amen Chorus at the end. In between are moments of transcendence, loss, and deeply-felt awe—what makes a classic a classic.

Performed in Princeton and Newark

Handel’s Messiah

New Jersey Symphony Holiday Tradition

Anthony Parnther conductor

Caitlin Gotimer soprano

Maria Dominique Lopez mezzo-soprano

Orson Van Gay II tenor

Shyheim Selvan Hinnant bass-baritone

Montclair State University Singers | Heather J. Buchanan, director

New Jersey Symphony

Handel’s Messiah embraces every emotion, from the first voice singing “Comfort ye,” inviting you to step aside from the season’s frenzy, to the riveting Amen Chorus at the end. In between are moments of transcendence, loss, and deeply-felt awe—what makes a classic a classic.

Performed in Princeton and Newark

Randall Goosby Returns

New Jersey Symphony Classical

Xian Zhang conductor

Randall Goosby violin

New Jersey Symphony

- Jean Sibelius Finlandia

Eight minutes that saved a nation. When Finland wrestled itself free from the Russian bear, Sibelius’ music was the Finns’ call to courage.

- Samuel Barber Violin Concerto

The most gorgeous violin concerto of the 20th century: the first two movements exquisitely touching, and the third a wild sprint for only the bravest of soloists.

- Pytor Ilyich Tchaikovsky Symphony No. 2, “Ukrainian”

Three Ukrainian folksongs were all Tchaikovsky needed for inspiration. From them, he spun his most joyful symphony.

Performed in New Brunswick, Princeton, Newark and Morristown

Randall Goosby Returns

New Jersey Symphony Classical

Xian Zhang conductor

Randall Goosby violin

New Jersey Symphony

- Jean Sibelius Finlandia

Eight minutes that saved a nation. When Finland wrestled itself free from the Russian bear, Sibelius’ music was the Finns’ call to courage.

- Samuel Barber Violin Concerto

The most gorgeous violin concerto of the 20th century: the first two movements exquisitely touching, and the third a wild sprint for only the bravest of soloists.

- Pytor Ilyich Tchaikovsky Symphony No. 2, “Ukrainian”

Three Ukrainian folksongs were all Tchaikovsky needed for inspiration. From them, he spun his most joyful symphony.

Performed in New Brunswick, Princeton, Newark and Morristown

Randall Goosby Returns

New Jersey Symphony Classical

Xian Zhang conductor

Randall Goosby violin

New Jersey Symphony

- Jean Sibelius Finlandia

Eight minutes that saved a nation. When Finland wrestled itself free from the Russian bear, Sibelius’ music was the Finns’ call to courage.

- Samuel Barber Violin Concerto

The most gorgeous violin concerto of the 20th century: the first two movements exquisitely touching, and the third a wild sprint for only the bravest of soloists.

- Pytor Ilyich Tchaikovsky Symphony No. 2, “Ukrainian”

Three Ukrainian folksongs were all Tchaikovsky needed for inspiration. From them, he spun his most joyful symphony.

Performed in New Brunswick, Princeton, Newark and Morristown

Randall Goosby Returns

New Jersey Symphony Classical

Xian Zhang conductor

Randall Goosby violin

New Jersey Symphony

- Jean Sibelius Finlandia

Eight minutes that saved a nation. When Finland wrestled itself free from the Russian bear, Sibelius’ music was the Finns’ call to courage.

- Samuel Barber Violin Concerto

The most gorgeous violin concerto of the 20th century: the first two movements exquisitely touching, and the third a wild sprint for only the bravest of soloists.

- Pytor Ilyich Tchaikovsky Symphony No. 2, “Ukrainian”

Three Ukrainian folksongs were all Tchaikovsky needed for inspiration. From them, he spun his most joyful symphony.

Performed in New Brunswick, Princeton, Newark and Morristown

Romeo & Juliet

Featuring The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey

Xian Zhang conductor

The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey

New Jersey Symphony

- Pytor Ilyich Tchaikovsky Romeo and Juliet Fantasy Overture

Tchaikovsky gives you all the passion and drama of Shakespeare’s two young lovers, as the New Jersey Symphony becomes a storyteller in real time.

- Sergei Prokofiev Selections from Romeo and Juliet

Considered too difficult, even undanceable at its unveiling, Prokofiev’s ballet with scene after scene of strikingly original music soon became the treasure of every ballet house the world over.

Performed in Newark and Red Bank

Romeo & Juliet

Featuring The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey

Xian Zhang conductor

The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey

New Jersey Symphony

- Pytor Ilyich Tchaikovsky Romeo and Juliet Fantasy Overture

Tchaikovsky gives you all the passion and drama of Shakespeare’s two young lovers, as the New Jersey Symphony becomes a storyteller in real time.

- Sergei Prokofiev Selections from Romeo and Juliet

Considered too difficult, even undanceable at its unveiling, Prokofiev’s ballet with scene after scene of strikingly original music soon became the treasure of every ballet house the world over.

Performed in Newark and Red Bank

Romeo & Juliet

Featuring The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey

Xian Zhang conductor

The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey

New Jersey Symphony

- Pytor Ilyich Tchaikovsky Romeo and Juliet Fantasy Overture

Tchaikovsky gives you all the passion and drama of Shakespeare’s two young lovers, as the New Jersey Symphony becomes a storyteller in real time.

- Sergei Prokofiev Selections from Romeo and Juliet

Considered too difficult, even undanceable at its unveiling, Prokofiev’s ballet with scene after scene of strikingly original music soon became the treasure of every ballet house the world over.

Performed in Newark and Red Bank

Romeo & Juliet

Featuring The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey

Xian Zhang conductor

The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey

New Jersey Symphony

- Pytor Ilyich Tchaikovsky Romeo and Juliet Fantasy Overture

Tchaikovsky gives you all the passion and drama of Shakespeare’s two young lovers, as the New Jersey Symphony becomes a storyteller in real time.

- Sergei Prokofiev Selections from Romeo and Juliet

Considered too difficult, even undanceable at its unveiling, Prokofiev’s ballet with scene after scene of strikingly original music soon became the treasure of every ballet house the world over.

Performed in Newark and Red Bank

2026 Lunar New Year Celebration

Celebration of the Year of the Horse

Sunny Xia conductor

Haochen Zhang piano

Peking University Alumni Chorus

New Jersey Symphony

Enjoy an evening of community and cultural exchange that is wonderful for families and children, as we celebrate the Year of the Horse. Seattle Symphony Associate Conductor Sunny Xia and Van Cliburn International Piano Competition Winner Haochen Zhang make their New Jersey Symphony debuts in this festive concert that celebrates music from East and West.

Performed in Newark

Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony

Time for Three Performs Contact

Markus Stenz conductor

Time for Three

Ranaan Meyer double bass | Nick Kendall violin | Charles Yang violin

New Jersey Symphony

- Richard Wagner Prelude to Act I of Lohengrin

It begins with the strings alone playing a whisperquiet passage of holy serenity. Soon the whole orchestra joins and builds in a full-throated cry. Wagner’s operatic stage is set for the arrival of the knight Lohengrin sent on a mission from God.

- Kevin Puts Contact

Time for Three, a self-described “classically trained garage band,” brings you the GRAMMY Award-winning concerto written for them by Pulitzer Prize-winning composer Kevin Puts. Created during the isolation of the early pandemic, Contact is “an expression of yearning for the fundamental need” of human connection.

- Ludwig van Beethoven Symphony No. 5

Four notes—dah, dah, dah, DAH—launched Beethoven’s Fifth in 1808 and have stamped all of western classical music since.

Performed in Morristown and Newark

Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony

Time for Three Performs Contact

Markus Stenz conductor

Time for Three

Ranaan Meyer double bass | Nick Kendall violin | Charles Yang violin

New Jersey Symphony

- Richard Wagner Prelude to Act I of Lohengrin

It begins with the strings alone playing a whisperquiet passage of holy serenity. Soon the whole orchestra joins and builds in a full-throated cry. Wagner’s operatic stage is set for the arrival of the knight Lohengrin sent on a mission from God.

- Kevin Puts Contact

Time for Three, a self-described “classically trained garage band,” brings you the GRAMMY Award-winning concerto written for them by Pulitzer Prize-winning composer Kevin Puts. Created during the isolation of the early pandemic, Contact is “an expression of yearning for the fundamental need” of human connection.

- Ludwig van Beethoven Symphony No. 5

Four notes—dah, dah, dah, DAH—launched Beethoven’s Fifth in 1808 and have stamped all of western classical music since.

Performed in Morristown and Newark

Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony

Time for Three Performs Contact

Markus Stenz conductor

Time for Three

Ranaan Meyer double bass | Nick Kendall violin | Charles Yang violin

New Jersey Symphony

- Richard Wagner Prelude to Act I of Lohengrin

It begins with the strings alone playing a whisperquiet passage of holy serenity. Soon the whole orchestra joins and builds in a full-throated cry. Wagner’s operatic stage is set for the arrival of the knight Lohengrin sent on a mission from God.

- Kevin Puts Contact

Time for Three, a self-described “classically trained garage band,” brings you the GRAMMY Award-winning concerto written for them by Pulitzer Prize-winning composer Kevin Puts. Created during the isolation of the early pandemic, Contact is “an expression of yearning for the fundamental need” of human connection.

- Ludwig van Beethoven Symphony No. 5

Four notes—dah, dah, dah, DAH—launched Beethoven’s Fifth in 1808 and have stamped all of western classical music since.

Performed in Morristown and Newark

Bartók’s Concerto

for Orchestra

New Jersey Symphony Classical

Ruth Reinhardt conductor

Eva Gevorgyan piano

New Jersey Symphony

- Béla Bartók Romanian Folk Dances

Informed by his numerous research trips across Hungary, this short and spry set of folk dances bursts with Transylvanian flavor and energy.

- Frédéric Chopin Piano Concerto No. 2

There are moments here that make time, and your breath, stand still. If ever you need evidence of the human spirit’s capacity for beauty, look to this remarkable creation of 20-year-old Chopin.

- Béla Bartók Concerto for Orchestra

Every section of the orchestra gets the spotlight to dazzling effect, and the Concerto’s last moments are some of the most thrilling in all classical music.

Performed in Newark, Princeton, Red Bank and New Brunswick

Bartók’s Concerto

for Orchestra

New Jersey Symphony Classical

Ruth Reinhardt conductor

Eva Gevorgyan piano

New Jersey Symphony

- Béla Bartók Romanian Folk Dances

Informed by his numerous research trips across Hungary, this short and spry set of folk dances bursts with Transylvanian flavor and energy.

- Frédéric Chopin Piano Concerto No. 2

There are moments here that make time, and your breath, stand still. If ever you need evidence of the human spirit’s capacity for beauty, look to this remarkable creation of 20-year-old Chopin.

- Béla Bartók Concerto for Orchestra

Every section of the orchestra gets the spotlight to dazzling effect, and the Concerto’s last moments are some of the most thrilling in all classical music.

Performed in Newark, Princeton, Red Bank and New Brunswick

Bartók’s Concerto

for Orchestra

New Jersey Symphony Classical

Ruth Reinhardt conductor

Eva Gevorgyan piano

New Jersey Symphony

- Béla Bartók Romanian Folk Dances

Informed by his numerous research trips across Hungary, this short and spry set of folk dances bursts with Transylvanian flavor and energy.

- Frédéric Chopin Piano Concerto No. 2

There are moments here that make time, and your breath, stand still. If ever you need evidence of the human spirit’s capacity for beauty, look to this remarkable creation of 20-year-old Chopin.

- Béla Bartók Concerto for Orchestra

Every section of the orchestra gets the spotlight to dazzling effect, and the Concerto’s last moments are some of the most thrilling in all classical music.

Performed in Newark, Princeton, Red Bank and New Brunswick

Bartók’s Concerto

for Orchestra

New Jersey Symphony Classical

Ruth Reinhardt conductor

Eva Gevorgyan piano

New Jersey Symphony

- Béla Bartók Romanian Folk Dances

Informed by his numerous research trips across Hungary, this short and spry set of folk dances bursts with Transylvanian flavor and energy.

- Frédéric Chopin Piano Concerto No. 2

There are moments here that make time, and your breath, stand still. If ever you need evidence of the human spirit’s capacity for beauty, look to this remarkable creation of 20-year-old Chopin.

- Béla Bartók Concerto for Orchestra

Every section of the orchestra gets the spotlight to dazzling effect, and the Concerto’s last moments are some of the most thrilling in all classical music.

Performed in Newark, Princeton, Red Bank and New Brunswick

Beethoven’s “Pastoral” Symphony

New Jersey Symphony Classical

Xian Zhang conductor

Juan Esteban Martinez clarinet

New Jersey Symphony

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Divertimento in D Major, K. 136

The spotlight opens on the New Jersey Symphony’s virtuoso strings playing the sunniest music Mozart ever created.

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Clarinet Concerto

Principal Clarinet Juan Esteban Martinez will shine in this sunny crown jewel of the clarinet repertoire, which was written for an earlier iteration of the modern clarinet.

- Ludwig van Beethoven Symphony No. 6, “Pastoral”

His greatest inspiration came from long walks in nature, score paper, and pencil stuffed in his pocket. Beethoven takes us with him in his Sixth, his music full of open-air melodies, and the drama of a ferocious storm.

Performed in Newark and Morristown

Discover Beethoven’s “Pastoral” Symphony

New Jersey Symphony Family Concert

Xian Zhang conductor

New Jersey Symphony

Discover the storytelling power of classical music! Beethoven’s “Pastoral” Symphony was one of his only works that depicts very specific scenes and storylines, which we’ll dive into measure by measure in this concert.

Performed in Newark

Beethoven’s “Pastoral” Symphony

New Jersey Symphony Classical

Xian Zhang conductor

Juan Esteban Martinez clarinet

New Jersey Symphony

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Divertimento in D Major, K. 136

The spotlight opens on the New Jersey Symphony’s virtuoso strings playing the sunniest music Mozart ever created.

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Clarinet Concerto

Principal Clarinet Juan Esteban Martinez will shine in this sunny crown jewel of the clarinet repertoire, which was written for an earlier iteration of the modern clarinet.

- Ludwig van Beethoven Symphony No. 6, “Pastoral”

His greatest inspiration came from long walks in nature, score paper, and pencil stuffed in his pocket. Beethoven takes us with him in his Sixth, his music full of open-air melodies, and the drama of a ferocious storm.

Performed in Newark and Morristown

Beethoven’s “Pastoral” Symphony

New Jersey Symphony Classical

Xian Zhang conductor

Juan Esteban Martinez clarinet

New Jersey Symphony

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Divertimento in D Major, K. 136

The spotlight opens on the New Jersey Symphony’s virtuoso strings playing the sunniest music Mozart ever created.

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Clarinet Concerto

Principal Clarinet Juan Esteban Martinez will shine in this sunny crown jewel of the clarinet repertoire, which was written for an earlier iteration of the modern clarinet.

- Ludwig van Beethoven Symphony No. 6, “Pastoral”

His greatest inspiration came from long walks in nature, score paper, and pencil stuffed in his pocket. Beethoven takes us with him in his Sixth, his music full of open-air melodies, and the drama of a ferocious storm.

Performed in Newark and Morristown

Xian Conducts

Prokofiev & Strauss

New Jersey Symphony Classical

Xian Zhang conductor

Francesca Dego violin

New Jersey Symphony

- Anton Webern Im Sommerwind

A lovingly lush hymn to the charms of summer, written just before Webern helped stand traditional classical music on its head.

- Sergei Prokofiev Violin Concerto No. 2

It opens with a wisp of melancholy Russian folksong and closes with castanets and Spanish flair, creating fireworks for a world-class violinist and orchestra.

- Richard Strauss Ein Heldenleben

Orchestras love this ode to “A Hero’s Life” for its bold, voluptuous sweep, created by Strauss as a musical pat on his own back.

Performed in Newark and Red Bank

Xian Conducts

Prokofiev & Strauss

New Jersey Symphony Classical

Xian Zhang conductor

Francesca Dego violin

New Jersey Symphony

- Anton Webern Im Sommerwind

A lovingly lush hymn to the charms of summer, written just before Webern helped stand traditional classical music on its head.

- Sergei Prokofiev Violin Concerto No. 2

It opens with a wisp of melancholy Russian folksong and closes with castanets and Spanish flair, creating fireworks for a world-class violinist and orchestra.

- Richard Strauss Ein Heldenleben

Orchestras love this ode to “A Hero’s Life” for its bold, voluptuous sweep, created by Strauss as a musical pat on his own back.

Performed in Newark and Red Bank

Xian Conducts

Prokofiev & Strauss

New Jersey Symphony Classical

Xian Zhang conductor

Francesca Dego violin

New Jersey Symphony

- Anton Webern Im Sommerwind

A lovingly lush hymn to the charms of summer, written just before Webern helped stand traditional classical music on its head.

- Sergei Prokofiev Violin Concerto No. 2

It opens with a wisp of melancholy Russian folksong and closes with castanets and Spanish flair, creating fireworks for a world-class violinist and orchestra.

- Richard Strauss Ein Heldenleben

Orchestras love this ode to “A Hero’s Life” for its bold, voluptuous sweep, created by Strauss as a musical pat on his own back.

Performed in Newark and Red Bank

Mozart’s Requiem

New Jersey Symphony Classical

Xian Zhang conductor

Mei Gui Zhang soprano

Taylor Raven mezzo-soprano

Eric Ferring tenor

Dashon Burton bass-baritone

Montclair State University Chorale | Heather J. Buchanan, director

New Jersey Symphony

- Gabriel Fauré Pavane

A slowly winding melody that started as a simple little five-minute piano solo. But when Fauré orchestrated his Pavane and added the rich sound of a chorus, he made magic and his greatest hit.

- Gustav Mahler Songs of a Wayfarer

Come enjoy one of the finest voices in America: bass-baritone Dashon Burton sings the suite of beautiful songs Mahler wrote as he took solace in nature after being spurned in love.

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Requiem

A swansong full of fire, grace, and a transcendent prayer that the human spirit will live on. Mozart’s Requiem was left maddeningly incomplete at his all-too-early death, but is nevertheless his final masterpiece.

Performed in Newark and New Brunswick

Mozart’s Requiem

New Jersey Symphony Classical

Xian Zhang conductor

Mei Gui Zhang soprano

Taylor Raven mezzo-soprano

Eric Ferring tenor

Dashon Burton bass-baritone

Montclair State University Chorale | Heather J. Buchanan, director

New Jersey Symphony

- Gabriel Fauré Pavane

A slowly winding melody that started as a simple little five-minute piano solo. But when Fauré orchestrated his Pavane and added the rich sound of a chorus, he made magic and his greatest hit.

- Gustav Mahler Songs of a Wayfarer

Come enjoy one of the finest voices in America: bass-baritone Dashon Burton sings the suite of beautiful songs Mahler wrote as he took solace in nature after being spurned in love.

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Requiem

A swansong full of fire, grace, and a transcendent prayer that the human spirit will live on. Mozart’s Requiem was left maddeningly incomplete at his all-too-early death, but is nevertheless his final masterpiece.

Performed in Newark and New Brunswick

Mozart’s Requiem

New Jersey Symphony Classical

Xian Zhang conductor

Mei Gui Zhang soprano

Taylor Raven mezzo-soprano

Eric Ferring tenor

Dashon Burton bass-baritone

Montclair State University Chorale | Heather J. Buchanan, director

New Jersey Symphony

- Gabriel Fauré Pavane

A slowly winding melody that started as a simple little five-minute piano solo. But when Fauré orchestrated his Pavane and added the rich sound of a chorus, he made magic and his greatest hit.

- Gustav Mahler Songs of a Wayfarer

Come enjoy one of the finest voices in America: bass-baritone Dashon Burton sings the suite of beautiful songs Mahler wrote as he took solace in nature after being spurned in love.

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Requiem

A swansong full of fire, grace, and a transcendent prayer that the human spirit will live on. Mozart’s Requiem was left maddeningly incomplete at his all-too-early death, but is nevertheless his final masterpiece.

Performed in Newark and New Brunswick

Joshua Bell Leads Mendelssohn’s “Italian”

New Jersey Symphony Classical

Joshua Bell conductor & violin

New Jersey Symphony

- Felix Mendelssohn The Hebrides (Fingal’s Cave)

The music swells and surges just as the waves off Scotland’s coast carried the young Mendelssohn past moody cliffs and caves and sent him reaching for his score paper.

- Édouard Lalo Symphonie espagnole

Though called a “symphony,” this is where superstar Joshua Bell stands and lets his Stradivarius violin sing the silvery songs of Spain.

- Felix Mendelssohn Symphony No. 4, “Italian”

“The jolliest piece I’ve ever done,” wrote an ecstatic young Mendelssohn to his parents back in Berlin, after arriving in Italy and falling in love with its sunshine, sidewalk tunes, coast, and effervescent colors—all of which he poured into his Fourth Symphony.

Performed in Newark, Princeton and Morristown

Joshua Bell Leads Mendelssohn’s “Italian”

New Jersey Symphony Classical

Joshua Bell conductor & violin

New Jersey Symphony

- Felix Mendelssohn The Hebrides (Fingal’s Cave)

The music swells and surges just as the waves off Scotland’s coast carried the young Mendelssohn past moody cliffs and caves and sent him reaching for his score paper.

- Édouard Lalo Symphonie espagnole

Though called a “symphony,” this is where superstar Joshua Bell stands and lets his Stradivarius violin sing the silvery songs of Spain.

- Felix Mendelssohn Symphony No. 4, “Italian”

“The jolliest piece I’ve ever done,” wrote an ecstatic young Mendelssohn to his parents back in Berlin, after arriving in Italy and falling in love with its sunshine, sidewalk tunes, coast, and effervescent colors—all of which he poured into his Fourth Symphony.

Performed in Newark, Princeton and Morristown

Joshua Bell Leads Mendelssohn’s “Italian”

New Jersey Symphony Classical

Joshua Bell conductor & violin

New Jersey Symphony

- Felix Mendelssohn The Hebrides (Fingal’s Cave)

The music swells and surges just as the waves off Scotland’s coast carried the young Mendelssohn past moody cliffs and caves and sent him reaching for his score paper.

- Édouard Lalo Symphonie espagnole

Though called a “symphony,” this is where superstar Joshua Bell stands and lets his Stradivarius violin sing the silvery songs of Spain.

- Felix Mendelssohn Symphony No. 4, “Italian”

“The jolliest piece I’ve ever done,” wrote an ecstatic young Mendelssohn to his parents back in Berlin, after arriving in Italy and falling in love with its sunshine, sidewalk tunes, coast, and effervescent colors—all of which he poured into his Fourth Symphony.

Performed in Newark, Princeton and Morristown

Joshua Bell Leads Mendelssohn’s “Italian”

New Jersey Symphony Classical

Joshua Bell conductor & violin

New Jersey Symphony

- Felix Mendelssohn The Hebrides (Fingal’s Cave)

The music swells and surges just as the waves off Scotland’s coast carried the young Mendelssohn past moody cliffs and caves and sent him reaching for his score paper.

- Édouard Lalo Symphonie espagnole

Though called a “symphony,” this is where superstar Joshua Bell stands and lets his Stradivarius violin sing the silvery songs of Spain.

- Felix Mendelssohn Symphony No. 4, “Italian”

“The jolliest piece I’ve ever done,” wrote an ecstatic young Mendelssohn to his parents back in Berlin, after arriving in Italy and falling in love with its sunshine, sidewalk tunes, coast, and effervescent colors—all of which he poured into his Fourth Symphony.

Performed in Newark, Princeton and Morristown

Star Wars: The Last Jedi in Concert

New Jersey Symphony at the Movies

Constantine Kitsopoulos conductor

New Jersey Symphony

Don’t miss this big-screen battle with the score performed live by the New Jersey Symphony. The Resistance is in desperate need of help when they find themselves impossibly pursued by the First Order. While Rey travels to a remote planet called Ahch-To to recruit Luke Skywalker to the Resistance, Finn and Rose, a mechanic, go on their own mission in the hopes of helping the Resistance finally escape the First Order. But everyone finds themselves on the salt-planet of Crait for a last stand.

Performed in Red Bank, Newark and New Brunswick

Star Wars: The Last Jedi in Concert

New Jersey Symphony at the Movies

Constantine Kitsopoulos conductor

New Jersey Symphony

Don’t miss this big-screen battle with the score performed live by the New Jersey Symphony. The Resistance is in desperate need of help when they find themselves impossibly pursued by the First Order. While Rey travels to a remote planet called Ahch-To to recruit Luke Skywalker to the Resistance, Finn and Rose, a mechanic, go on their own mission in the hopes of helping the Resistance finally escape the First Order. But everyone finds themselves on the salt-planet of Crait for a last stand.

Performed in Red Bank, Newark and New Brunswick

Star Wars: The Last Jedi in Concert

New Jersey Symphony at the Movies

Constantine Kitsopoulos conductor

New Jersey Symphony

Don’t miss this big-screen battle with the score performed live by the New Jersey Symphony. The Resistance is in desperate need of help when they find themselves impossibly pursued by the First Order. While Rey travels to a remote planet called Ahch-To to recruit Luke Skywalker to the Resistance, Finn and Rose, a mechanic, go on their own mission in the hopes of helping the Resistance finally escape the First Order. But everyone finds themselves on the salt-planet of Crait for a last stand.

Performed in Red Bank, Newark and New Brunswick

Symphonie fantastique

Season Finale | New Jersey Symphony Classical

Xian Zhang conductor

Emanuel Ax piano

New Jersey Symphony

- Allison Loggins-Hull New Work (World Premiere, New Jersey Symphony Commission)

You may have seen her performing with Lizzo at the GRAMMYs, or heard her on the soundtrack to The Lion King, or loved her Can You See? performed by the New Jersey Symphony last fall. Be the first to hear our Resident Artistic Partner’s latest creation.

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Piano Concerto No. 22

Mozart in his late 20s took a tune he wrote when he was eight and turned it into this half-hour masterpiece, the second of its three movements so moving that its first audience demanded a repeat.

- Hector Berlioz Symphonie fantastique

Smitten with unrequited love, Berlioz funneled all his frustrations and utter mind-blowing genius into a whirlwind of orchestral color.

Performed in New Brunswick, Princeton, Red Bank and Newark

Symphonie fantastique

Season Finale | New Jersey Symphony Classical

Xian Zhang conductor

Emanuel Ax piano

New Jersey Symphony

- Allison Loggins-Hull New Work (World Premiere, New Jersey Symphony Commission)

You may have seen her performing with Lizzo at the GRAMMYs, or heard her on the soundtrack to The Lion King, or loved her Can You See? performed by the New Jersey Symphony last fall. Be the first to hear our Resident Artistic Partner’s latest creation.

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Piano Concerto No. 22

Mozart in his late 20s took a tune he wrote when he was eight and turned it into this half-hour masterpiece, the second of its three movements so moving that its first audience demanded a repeat.

- Hector Berlioz Symphonie fantastique

Smitten with unrequited love, Berlioz funneled all his frustrations and utter mind-blowing genius into a whirlwind of orchestral color.

Performed in New Brunswick, Princeton, Red Bank and Newark

Symphonie fantastique

Season Finale | New Jersey Symphony Classical

Xian Zhang conductor

Emanuel Ax piano

New Jersey Symphony

- Allison Loggins-Hull New Work (World Premiere, New Jersey Symphony Commission)

You may have seen her performing with Lizzo at the GRAMMYs, or heard her on the soundtrack to The Lion King, or loved her Can You See? performed by the New Jersey Symphony last fall. Be the first to hear our Resident Artistic Partner’s latest creation.

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Piano Concerto No. 22

Mozart in his late 20s took a tune he wrote when he was eight and turned it into this half-hour masterpiece, the second of its three movements so moving that its first audience demanded a repeat.

- Hector Berlioz Symphonie fantastique

Smitten with unrequited love, Berlioz funneled all his frustrations and utter mind-blowing genius into a whirlwind of orchestral color.

Performed in New Brunswick, Princeton, Red Bank and Newark

Symphonie fantastique

Season Finale | New Jersey Symphony Classical

Xian Zhang conductor

Emanuel Ax piano

New Jersey Symphony

- Allison Loggins-Hull New Work (World Premiere, New Jersey Symphony Commission)

You may have seen her performing with Lizzo at the GRAMMYs, or heard her on the soundtrack to The Lion King, or loved her Can You See? performed by the New Jersey Symphony last fall. Be the first to hear our Resident Artistic Partner’s latest creation.

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Piano Concerto No. 22

Mozart in his late 20s took a tune he wrote when he was eight and turned it into this half-hour masterpiece, the second of its three movements so moving that its first audience demanded a repeat.

- Hector Berlioz Symphonie fantastique

Smitten with unrequited love, Berlioz funneled all his frustrations and utter mind-blowing genius into a whirlwind of orchestral color.

Performed in New Brunswick, Princeton, Red Bank and Newark

Ben Folds with the New Jersey Symphony

Ben Folds performs his greatest hits!

Ben Folds guest artist

New Jersey Symphony

Emmy-nominated singer-songwriter-composer Ben Folds joins the New Jersey Symphony for a unique and unforgettable performance of music from across his career. Widely regarded as one of the major musical influences of our generation, Folds’ enormous body of genre-bending music includes pop albums with Ben Folds Five, multiple solo albums, and numerous collaborative records. His latest album, 2023’s What Matters Most, is a blend of piano-driven pop rock songs, while his 2015 Concerto for Piano and Orchestra soared to #1 on both the Billboard classical and classical crossover charts. He released his first Christmas album in 2024 and last Fall recorded a live album slated for release in 2025 with the National Symphony Orchestra (NSO) at The Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C., where he served for eight years as the first artistic advisor to the NSO.

Performed in Newark and New Brunswick

Ben Folds with the New Jersey Symphony

Ben Folds performs his greatest hits!

Ben Folds guest artist

New Jersey Symphony

Emmy-nominated singer-songwriter-composer Ben Folds joins the New Jersey Symphony for a unique and unforgettable performance of music from across his career. Widely regarded as one of the major musical influences of our generation, Folds’ enormous body of genre-bending music includes pop albums with Ben Folds Five, multiple solo albums, and numerous collaborative records. His latest album, 2023’s What Matters Most, is a blend of piano-driven pop rock songs, while his 2015 Concerto for Piano and Orchestra soared to #1 on both the Billboard classical and classical crossover charts. He released his first Christmas album in 2024 and last Fall recorded a live album slated for release in 2025 with the National Symphony Orchestra (NSO) at The Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C., where he served for eight years as the first artistic advisor to the NSO.

Performed in Newark and New Brunswick

Program Notes | Hugh Wolff Conducts Beethoven & Mozart

Ludwig van Beethoven: Overture to Egmont, Op. 84

Beethoven’s Overture to Egmont, Op. 84, is a powerful musico-dramatic statement inspired by one of Goethe’s great plays. Beethoven composed it as part of incidental music for an 1810 production of the drama. He identified strongly with Egmont’s themes: the perils of political intrigue, nascent nationalism, and liberation from tyranny. This dramatic overture is a splendid example of Beethoven’s ‘heroic’ style. The opening chords symbolize fate; the flowing string melody of the Allegro surges with forward momentum. A bright coda in F major represents victory over political oppression.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Piano Concerto No.25

Mozart’s Piano Concerto No.25 dates from the mid-1780s, when he was at the height of his success in Vienna. The concerto crowns several years when piano concertos dominated his output – more than symphony, more than chamber music, even more than opera. In the space of barely three years, he produced twelve masterpieces for piano and orchestra, every one of which remains in the repertoire. Some have called K.503 Mozart’s “Emperor” concerto, but it is even more aptly compared to his “Jupiter” Symphony: in the same key of C major, and with a melodic sweetness married to Olympian power. He establishes heroic character in the march-like opening. Listen for trumpets and drums; this is bright, assertive music. The pianist’s first entrance is almost a mini-cadenza. Mozart shows us a softer side in the pastoral Andante, which has wide melodic leaps that are almost operatic. A symphonic approach returns for the finale, where Mozart dazzles us with muscle and agility. It is a joyous ride.

Aaron Jay Kernis: Symphony No. 2

Maestro Wolff led the world premiere of Aaron Jay Kernis’s Symphony No. 2 in 1992, right here in Newark. At the time, Kernis was deeply affected by the Persian Gulf War and the escalating political situation in Bosnia. The opening “Alarm” is a high-energy paean that expresses his simultaneous fascination and horror with the technology of modern warfare. “Air/Ground” is both a quasi-military reference and a bow to the Baroque era, when composers wrote airs [melodies] above ostinato ground bass lines. This is the emotional core of the symphony. The finale, ‘Barricade,’ combines the intense emotion of the slow movement with the surging undercurrent of the first. Prominent brass and percussion emphasize the connection with warfare and the suffering it imposes.

Maurice Ravel: La Valse

The genesis of Ravel’s La Valse is complex, beginning in 1906 when he first considered a symphonic poem called Wien [Vienna]. When Serge Diaghilev commissioned a ballet from Ravel in 1919, he dusted off the sketches and started serious work. The project derailed, precipitating a permanent breach between Ravel and Diaghilev. Ravel secured an orchestral performance in 1920, but had to wait until 1929 for a ballet production – when a different troupe staged it. Ravel customarily composed at the piano. Many of his compositions exist in versions for solo piano as well as orchestra, including Le Tombeau de Couperin, Pavane pour une infante défunte, and Valses nobles et sentimentales. Two prior versions of La Valse preceded the orchestral score: one for solo piano, the other for two pianos. Ravel’s orchestral La Valse (1920) has become a concert hall staple and is a brilliant showpiece. The ballet has attracted many celebrated choreographers, including George Balanchine and Frederick Ashton. No surprise there, for Ravel’s music is the essence of dance.

This information is provided solely as a service to and for the benefit of New Jersey Symphony subscribers and patrons. Any other use without express written permission is strictly forbidden.

-

Ludwig van Beethoven: Overture to Egmont, Op. 84

-

Ludwig van Beethoven

Born: December 16, 1770 in Bonn, Germany

Died: March 26, 1827 in Vienna, Austria

Composed: October 1809 to June 1810

World Premiere: June 15, 1810 in Vienna, Austria

Duration: 9 minutes

Instrumentation: woodwinds in pairs, four horns, two trumpets, timpani and stringsJohann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832) was the most important figure in German literary romanticism. He was also Beethoven’s favorite writer. Thus in 1809, when the director of Vienna's Burgtheater decided to stage revivals of Goethe's Egmont and Friedrich Schiller's William Tell with new incidental music for both plays, Beethoven was keen to secure the commission.

Beethoven identified strongly with both plays’ themes: the perils of political intrigue, nascent nationalism, and liberation from tyranny. But his Viennese colleague Adalbert Gyrowetz was assigned the Tell music (which preceded Rossini's opera by two decades). Thus it fell to Beethoven to compose nearly 40 minutes of music for Egmont, a drama that was deemed unsuitable for music. Beethoven, of course, proved that opinion wrong.

Historical resonance

Egmont takes place during the 16th century Counter-Reformation, when the Low Countries were under Spanish Habsburg rule. The hero, Count Egmont, perceives that the Netherlands will revolt and eventually free itself from Spanish domination, but his own courageous stand costs him his life. He is executed by the Hapsburg Duke of Alva. His spirit endures to help his people to overthrow the despotic ruler. Egmont's message was fully in keeping with Beethoven’s aversion to the Napoleonic juggernaut.Destiny and drama in nine minutes

The Overture to Egmont is a superb example of Beethoven's "heroic" style, along with the Fifth Symphony and the "Emperor" Concerto. In essence, the overture is a microcosm of Goethe’s drama. Formally, it comprises a slow introduction to a sonata-allegro movement; however, Beethoven adjusts sonata form to accommodate aspects of the underlying story.Beethoven's dark, dramatic music is fraught with the destiny of its hero. The opening chords symbolize fate; the flowing string theme of the Allegro has a surging forward momentum that carries us with the drama. The bright coda in F major represents victory over the political oppressors, and so on. Such emphasis on programmatic content was fairly new in 1809 and is particularly unusual in Beethoven. In that sense, it demonstrates a heady romantic streak in Beethoven that comes as a surprise so early in the century.

-

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Piano Concerto No. 25 in C Major, K. 503

-

Wolfgang Amadèus Mozart

Born: January 27, 1756 in Salzburg, Austria

Died: December 5, 1791 in Vienna, Austria

Composed: November and December 1786

World Premiere: December 1786 in Vienna, Austria

Duration: 30 minutes

Instrumentation: flute, two oboes, two bassoons, two horns, two trumpets, timpani, solo piano, and stringsSeventeen eighty-six, the year of The Marriage of Figaro, was exceptionally productive for Mozart. In addition to the opera, he was able to complete a number of splendid chamber works and several piano concerti. Arthur Hutchings has observed that the C major concerto, K. 503, "marks the end of Mozart's period of `stardom' as Vienna's performer/composer." While he produced two additional keyboard concerti before his death, the circumstances of those that followed (K. 537 in D, "Coronation," and K. 595 in B-flat) are so different from those that preceded them that Hutchings's observation is apt. In many ways, K. 503 crowns the entire magnificent cycle of Mozart's piano concerti.

Hutchings calls this piece "Mozart's `Emperor' Concerto; so does Cuthbert Girdlestone, author of another venerable volume devoted exclusively to discussion of Mozart's keyboard concerti. The piece is an enormous achievement, with a spaciousness, breadth and power all expressed with a heroism that does indeed look forward to Beethoven. Majestic seems to be the best description. Mozart employed his largest concerto orchestra to support the piano in K.503, excepting only No. 24 in C minor, K. 491, which calls for clarinets as well as oboes. But the first movement of K. 503 is the lengthiest movement that Mozart ever composed.

A bold, assertive C major opening built on arpeggiated tonic chords set a forthright military tone characteristic of many of Mozart's first movements. A secondary fanfare theme that foreshadows the opening phrase of the "Marseillaise" serves as an important developmental building block. Such Beethovenian gestures are liberally interspersed with delightful little melodies of Mozartian simplicity and appeal. Pianist and author Charles Rosen has observed:

In K.503, the renunciation of harmonic color is already a marked characteristic: almost all the shadings arise from a simple alternation of major and minor. . . . [This] alternation is the dominant color of K. 503, and a prime element of the structure as well.

Using Rosen's observation as a listening guideline reveals startling parallels among the three movements, and illustrates with what elemental and economical means Mozart constructs the most elaborate and imposing of his musical structures. In the playful rondo that closes the concerto, his lighter tone never compromises the grandeur and dignity of the whole.

No cadenza by Mozart survives for this concerto, because he composed it for himself and his custom in concert was to improvise. (Written-out cadenzas survive for other concertos, usually those he wrote for his gifted students.) Mr. Goode performs his own original cadenza.

-

Aaron Jay Kernis: Symphony No. 2

-

Aaron Jay Kernis

Born: January 15, 1960 in Bensalem Township, PA

Composed: 1991

World Premiere: January 15, 1992 in Newark, NJ. Hugh Wolff conducted the New Jersey Symphony.

Duration: 26 minutes

Instrumentation: three flutes (third doubling piccolo), two oboes, English horn, two clarinets (one in B-flat, one in A), bass clarinet, three bassoons (third doubling contrabassoon), four horns in F, four trumpets in C, four trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (requiring four players; the battery includes snare drum, piccolo & high snare drum, tenor drum, small and large bass drum, medium log drum, brake drum, bongos, congas, wood blocks, reco reco, lead pipe, mounted handbells, cow bells, thunder sheet, crotales, cabasa, small and high triangles, China boy cymbal, small, medium and large cymbals, small and medium crash cymbals, ride cymbal, vibraphone, xylophone, glockenspiel, marimba, chimes, medium and large tam tams, and tom toms), harp, piano, and stringsAaron Jay Kernis was an up-and-coming American composer long before he snared the 1998 Pulitzer Prize in music for his Second String Quartet, or the 2002 Grawemeyer Award for Music Composition. In the two decades since then, he has consolidated his position as one of America’s leading composers. Kernis’s education and stylistic mentors were widespread and eclectic, including study with John Adams at the San Francisco Conservatory, Charles Wuorinen and Elias Tanenbaum at Manhattan School of Music, and Morton Subotnick and Jacob Druckman at Yale. Kernis’s music is equally eclectic, ranging from the profound and spiritual works to those with gleeful abandon. His First String Quartet, composed when he was thirty, is a large-scale, traditional multi-movement work that shows both respect for and command of traditional form. At the same time, its slow movement, which Kernis arranged for string orchestra, brings to mind the music of such contemporary mystics as the Estonian Arvo Pärt and the Polish Henryk Mikolaj Górecki. By contrast, Le quattro stagioni dalla cucina futurismo [“The Four Seasons of Futurist Cuisine”] is a howlingly funny romp for narrator and piano trio. These diverse compositions reflect a composer with a broad emotional span.